Side A

Before I’m a fan of video games, first and foremost I’m a fan of music. I love listening to music, I love the chances I’ve had playing music, and I love experiencing music in levels beyond just the audio experience. One of my first concerts was now over a decade ago; I still remember seeing CHVRCHES months after my first breakup and all of us in attendance getting caught in a downpour as soon as the drop in “Clearest Blue” hit. Between my friendships, my travels, and just the way I view so much of the world now, I owe a lot of my current self to the kid who would sit at the car radio flipping through stations to find sounds that resonated, regardless of their release date or genre.

It’s also the initial love of music that led to my appreciation of TV, film, and eventually video games. Katamari Damacy is one of my favorite games partially due to its eclectic soundtrack, as are a majority of the games I look at in the ever rotating top ten list that I know exists for myself, but have never put to paper. So often for me, a game that can lack in tactile prowess can make up for it by having an effective soundtrack. Conversely, one of the things that’s kept me from going back to Street Fighter 6 for practice in this current season is the fact the core soundtrack disappointingly lacks any sort of punch that Capcom as a gaming music juggernaut is known for. Still fun to watch, but any attempts to lab it will require me adding my own soundtrack so I don’t have to hear “SURVIVALIST. HUNGRY LIKE A TIGER IS” any time I hit character select.

Rhythm games know all too well about how much the curation of sound is vital to their existence, next to the mechanical feel of “playing” the music chosen. From ParRappa the Rapper to Guitar Hero to Chuunithm, the genre has been able to solidify the key components of success: music that’s worth listening to and a gameplay that intuits the feel of being “part” of the song.

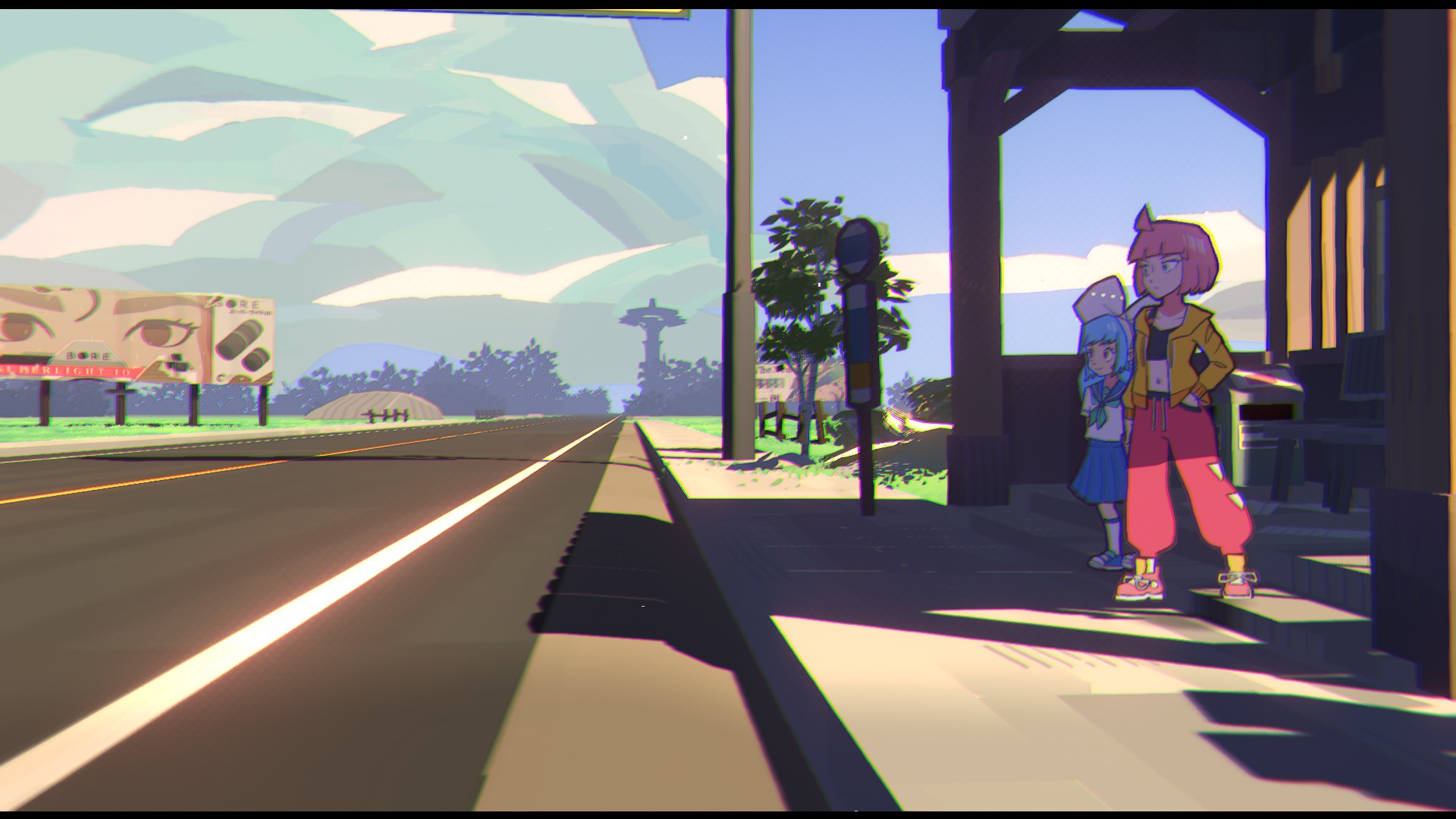

D-Cell’s UNBEATABLE is a rhythm game where music is illegal and you do crime. In this game you play as Beat, a young woman who sings in the band UNBEATABLE alongside the preteen Quaver on guitar, the explosive Clef on drums, and her reserved twin brother Treble on keyboard. The soundtrack is a wholly original collection of rock songs along with inclusions from other artists in the music and games sphere like Jamie Paige and 2mello. The rhythm gameplay itself is pretty simple: enemies, dubbed Silence, will approach Beat on a track from the outside of the screen towards the center. These enemies move in time to the music and are either on a top or bottom lane. Hit your button when the Silence arrives at a designated circle to beat them up and hit as many as possible to get through the song! Some notes require some kind of tap, others will need you to hold the button and release on time to register. Too many missed notes will result in a game over, so feel the beat and keep on trying!

There are options to set your controls to a variety of keystrokes aligned with the various approaches to rhythm gaming through a controller or keyboard; my layout maps the top lane notes to the triggers of my DualSense and the bottom lane notes to the face buttons and d-pad, similar to what I usually use for Taiko no Tatsujin. The higher difficulty beatmaps can be physically exhausting, so it’s nice to have the immediate option to try out layouts that can make subdivided notes a little easier to manage.

I do want to highlight the team in charge of structuring the various beatmaps for the game: Chi Xu, Cheryl, and TaroNuke show their love of the genre on their sleeves with the layouts of these songs. The only time I’ve ever heard rock in a rhythm game has been either in Guitar Hero or tap rhythm games like Osu! Tatakae! Ouendan! and its Western sibling Elite Beat Agents. There’s nothing that outright differentiates the genre from being included in other rhythm games, but there’s a lot of care in place to effectively highlight the feel of each song. “Empty Diary” is one of my favorite tracks and the higher difficulties do a good job of providing challenge without being a grueling test of endurance or fast track to arthritis. There are tracks that definitely lean into that Rhythm Pervert (affectionate?) mentality of playstyle, but it’s not something expected of you in normal gameplay.

The soundtrack has also been something that’s stuck with me for the better part of the last four years. Peak Divide, the in-studio band made up of composers Clara Maddux and Vasily Nikoleav with vocals from other members including producer Rachel Lake, have cultivated a sound that is so evocative of people getting into a garage and making music as a means of escape and expression. The song I had mentioned before, “Empty Diary,” opens with a strong guitar arpeggio followed by the tapping on a cymbal leading into the rest of the band. It’s the kind of intro I’ve heard at many a bar venue or music hall from a band I hadn’t heard until then and getting to figure out for the first time. The Pillows are an immediate inspiration gleaned from this production, as is apparent in the rest of the game and its ties to FLCL. The rest of the soundtrack continues to deliver hard hitting bangers like “Waiting” and “Sleeping In,” and the game also includes various remixes of these songs or nondiegetic tunes in the Arcade mode like the Tutorial song Proper Rhythm that uses a pretty funky groove with samples from a typing instructional video that also acts as a nod to the keyboard warriors keeping their hands on the home row.

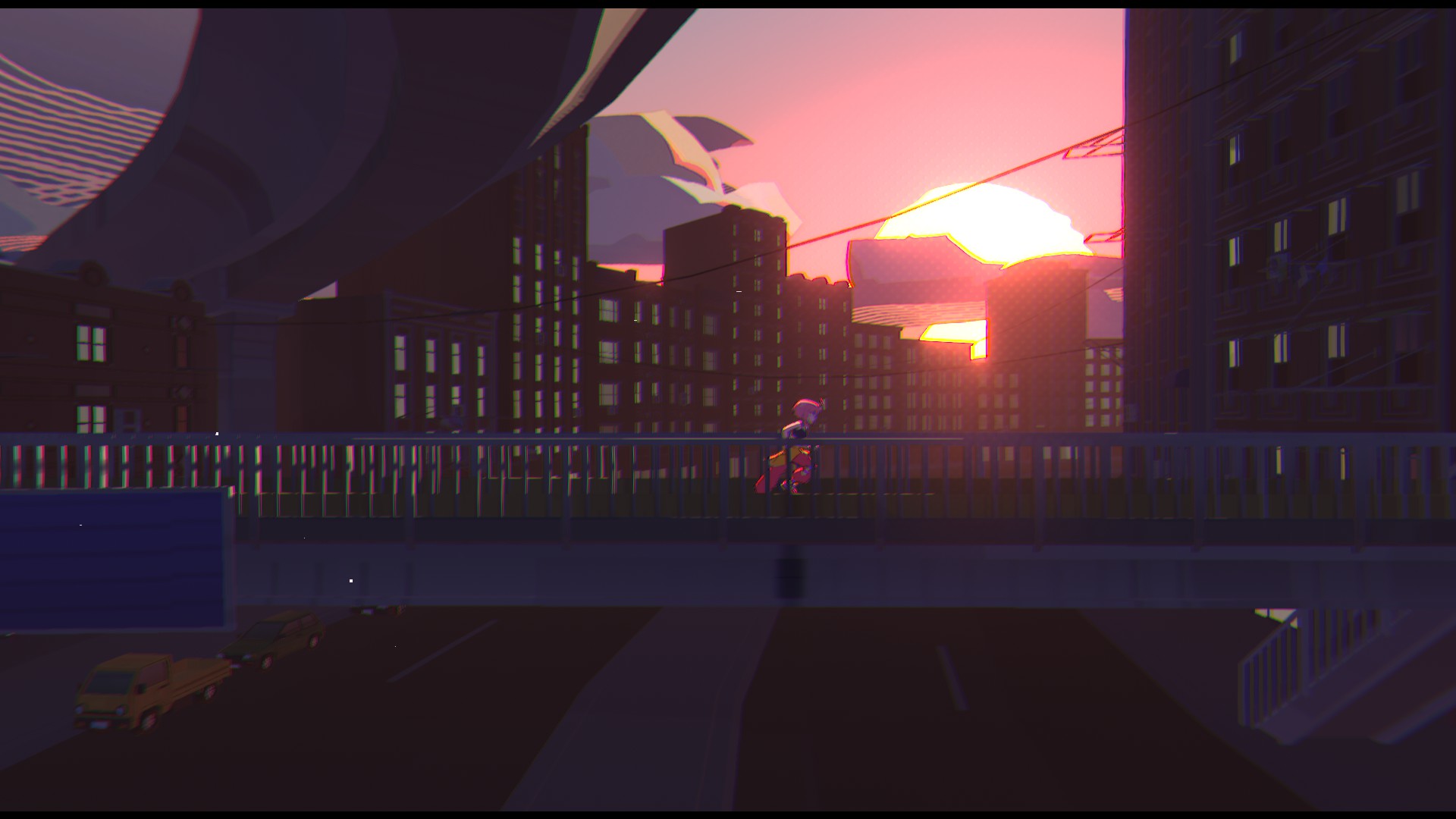

The audio has been a core feature of what makes UNBEATABLE so charming, but alongside that is the actual visuals which are so essential to the vibe. The game is unabashedly inspired by anime, its primary aesthetics most evocative of current Studio Trigger works to draw an immediate contemporary. Every character stands out in some way, be it Beat’s rough and tumble jumpsuit look with bright pink hair or Quaver’s distinct blue and white palette in both hair and dress. The additional characters come alive with their own visual personalities and are a blast to see sprinkled throughout the environments of the game. Environments are fully realized 3D spaces which creates a Paper Mario-esque storybook feel as you see your characters run around the space. The scenes themselves take heavy Japanese influence, at one point full on recreating a train station in Inaba, and the lighting becomes such a fun thing to notice throughout your time in the Story Mode. There can be a stillness captured in some scenes which is nice to sit in for a while. Unbeatable knows what it wants to sound like and look like, and there’s no hesitation in getting those pieces aligned when put in motion.

SIDE B – Spoilers for the story mode to UNBEATABLE

When you boot up the game for the first time, there’s a special introduction screen where the game asks about your own familiarity with rhythm games. Do you like them, do you feel skilled at them, and then calibrate the rhythm offset for you along with the flashiness of the on screen effects. The last few words in this opening scene are “THIS IS A STORY ABOUT LOSING YOUR WAY. IT’S NOT A LOVE STORY. NOT LIKE YOU’D THINK ANYWAY […] ALL STORIES ARE KIND OF LOVE STORIES. AT LEAST THE GOOD ONES ARE.” This initial introduction I felt was really well done. I can’t speak on the direct references that this game pulls on in terms of what might be in the team’s specific game bible, but since the first trailer I’ve been aware that UNBEATABLE has shades of FLCL and Scott Pilgrim in its palette. Two series that I had experienced at age twelve, a vulnerable age where the stories someone becomes really fascinated by and even passionate about take deep roots and compel that audience member to ask, “well what else?” A bit of an extrapolation, but that was about the age where I realized liking cartoons and video games wasn’t something I needed to give up at a security checkpoint before passing into adolescence. Suffice to say UNBEATABLE is a game that I felt primed to take in, enjoy, and fully engross myself in. To allow something so joyous about art and its process, warts and all, to move me to tears. That was not the experience I had with the Story Mode by its end.

UNBEATABLE’s Story Mode starts with Eve, the vocalist for the band One More Final, taking the stage for the last time. We then cut to Beat waking up beside a tree and running up to meet Quaver, unaware of who she or anyone else is. Beat has no recollection of what she was doing and proceeds to accompany Quaver who eventually goes to the abandoned concert hall her mother played her last show at. Performing for Beat, Quaver’s guitar strums bring forth the Silence, beast-like creatures who are drawn to music and are the reason used to outlaw music in its entirety in this world. Beat proceeds to follow Quaver along as they decide to rescue Treble and Clef from prison, and the eventual breakout leads to them forming a band and starting to tour across the local area. Eventually this trips the alert of HARM, the police force cracking down on any and all cases of sound-related crime, who start upping the ante on what it will take to cut UNBEATABLE down.

I need to take a minute to talk about Tenchi Muyo! More specifically, the overall franchise of media that Tenchi Muyo! has become over time. The core frame of the narrative is about a young man named Tenchi who becomes involved in the lives of various outer space women as they bring him along for adventures and shenanigans. This summary is concise not because of a lack of depth around the series, but because the idea is extrapolated on in nearly 30 years’ worth of OVAs, TV anime, drama CDs, and movies. For the Toonami faithful, you were most likely exposed to the original 6 episode OVA also known as Tenchi Muyo! Ryo-Ohki, the 26 episode series Tenchi Universe, and other series like Tenchi in Tokyo. All of these are part of the overall franchise, but key differences that can come up mainly lie in the characterization or overall atmosphere of what you’re watching. To what degree is Ryoko Hakubi an all powerful space pirate, is Tenchi himself a hapless hero caught in between the turmoil of the women he’s helping, those kinds of things. As Youtuber Hazel highlights in her video of the series, the level to which everyone is actually related to one another becomes different depending on what you’re watching. End of the day, the series is still capturing the hearts and minds of many fans regardless of what interpretation you manage to catch.

UNBEATABLE, as a narrative, feels caught in an issue of creating multiple interpretations, but all in one package rather than these separate iterations. The demo, UNBEATABLE [white label], came out years ago as the prelude to what this game would eventually be. Many of the songs in the game had these cutscenes introducing and concluding the rhythm sections, detailing parts of Beat’s inspirations for writing. The sparsity in this case was evocative and compelling to the structure. In the main game, it’s never fully explored that Beat writes her own music. Clef in Episode Four comments on her songwriting but at no point is it really brought up prior to that. These songs we hear in the action segments and in bigger setpieces of the game aren’t really brought up as to why they’re here, which isn’t out of the ordinary in most narrative rhythm games. PaRappa never takes a second to say “LeMmE JusT jot THIS doWn” after he raps with Cheap Cheap the Cooking Chicken, nor do most musicals actually title the music in-universe since the expression of emotion through song is understood as this natural occurrence in the laws of that world.

Overall I realized that the feeling of what this story was supposed to be got superseded by other ideas butting in and clogging each other up. This story wants to be about creation, it wants to be about losing yourself, it wants to fight the power. These are things that I love that come up in so much of the art I adore! Here though, I keep finding myself asking “why” or “how come” more often than I’m able to allow myself to run with the narrative. As someone who’s also a big pro wrestling fan, that feeling of being pulled out from the illusion sucks, and that moment hit me hard by the end of Chapter 4. After Chapter 3, we meet our heroes in a larger cityscape. At this point the band has started to gain notoriety and after playing some shows, are in the process of creating an album. Penny, one of the inmates from the prison in Chapter 2 who helps the crew escape, runs into Beat and offers to help with the production of the album. For the next four days, Beat ghosts the band, gets worse in practice, and is consumed at the idea of finishing this record. Clef has a heart to heart with her in the local batting cages using this Rhythm Heaven style minigame to get her point across.

I thought the idea was cool and I appreciate Clef as a headstrong character also knocking sense into the other headstrong character, but so much of that dialogue was tuned out because I tried to focus on the minigame. There’s parts of the game where if you fail a rhythm section, you will just get sent to the next part of the story with no option to retry the segment you just failed. It sucks! I hate the feeling that I can’t pick myself up after eating shit, something that I loved so dearly in the last game I reviewed where failure was applauded as much as succeeding! So rather than take in the narrative heft of whether the product or the process is the thing that matters most in the act of creation, I tapped circle to make sure I didn’t get a game over and skip that anyway. Then I fought some more cops, and our studio got blown up. Cut to chapter 5.

At its core, UNBEATABLE is proudly anti-authoritarian and anti-fascist. The only real interaction you have with police in this game is through fighting them, and the forces at HARM are also constantly reminded to be the villains without question. Beat, in every single interaction that she was with a member of authority, consistently reminds us that they are pieces of shit and horrible human beings. That part’s all well and fine, shoutout the cop slide. What ends up taking shape is this persecution complex, for a lack of a better word. Everything is against Beat, and since we only have Beat’s interpretation of the world she’s interacting with, then it’s easy to take that hostility at face value. People can be upset by her, but rarely, like in that batting cage segment, do we have anyone really push Beat on how she views the world. Again, this isn’t a plea to have Beat feel bad about The One Good Cop, but more having a curiosity as to why things are the way they are. Beat is thrown into this story with next to no knowledge of what’s going on, much like we are as the player, but then I felt like I had more questions about the world than Beat did and the frustrations came around the “why” of everything. Even if there were no concrete answer, to then at least have the “why” through the distorted lens of authority and scrutinize whether it was an explanation that people did feel complacent to uphold.

Seven years is a lot of time to work on something. In that time ideas can change, be reworked, be given new life, be dead in the water after an epiphany. This focus and obsession of time passing comes up several times throughout the game. At times it feels a little tongue in cheek, but there’s an earnestness to the fact this team spent so damn long crafting this idea. The fact this game is out at all is a miracle, let it be known. But the flaws I feel I keep running into about how this story is, what the focus is, the overall premise of UNBEATABLE, I hit this point where those frustrations feel less like me wanting to sit in critique and more eager to sit in with the staff to draw up stories. That I want to make a game that dedicates more time towards providing outlets to those who do harm. A story around a pain felt by everyone but spoken about by no one. o go out and craft something rather than say why this game isn’t evocative of the vision in my head. This isn’t my game though, and the time I sat with Beat and the others really reminded me of that by the end.

As I work through my feelings about this game, I do feel compelled to think about the students I work with, young people of color who are very well aware of how the world hates them but who have been brought up with just enough acceptance of the status quo that to resist authority requires teaching both the intrinsic moral and the practical application of unplugging, disconnecting, and reconvening. It’s the way that even with my lack of strict cybersecurity routine I’ll shoo away a discord reply asking me to join a test server because that doesn’t sit right. The core message of rebellion and doing what you love is something I want others to take on and love passionately as well. I think this game can be profound if you’re learning what adversity feels like for the first time. If the world looks full of enemies more than it does friends, then I can see someone resonating a lot with Beat.

I just can’t help but feel like I’m staring at a window, the lights on and the music inside just audible enough from the outside. “They must be having a good time,” I think to myself as I walk to my destination and look up the song playing because it’s by an artist I recognize or a band that I already listen to. I look at the staff, the inspirations, all of these separate pieces of the process to make this game and am so proud of what’s been created at the end in terms of the effort put in to create it. Why then, do I feel like this story lands flat? My initial draft of this review was caustic even, much more an open letter to RJ Lake and Andrew Tsai asking why couldn’t I understand this, even though I can see the blueprints and appreciate them? It sucks to have something that you’ve waited on, even put money into (two dollars, but in 2021 those were two of the maybe ten dollars I had to my name total), and get a product you like most of, but not all of. It’s not to say that RJ and Andrew are untalented either, if anything that’s refuted by the song credits and visual direction and every other piece of the game that they take a stake on. I don’t feel right calling RJ a bad writer for this story, when their expressions of isolation, worry, and perseverance in “Empty Diary” and “Mirror” are still rolling around in my head.

UNBEATABLE is something that reminded me I do like rhythm games. Its sound is one that’s been around with me ever since I listened to The Dream is Over by PUP for the first time back in 2017. It’s been in the periphery of my young adulthood, and its message of losing yourself and finding your voice has been in the back of my head for every job I got fired from, every friend I’ve had to lose, every night where I felt like the person I saw in the mirror was not the person I wanted to wake up the next morning. I think having this game a year before I enter my 30s, well traveled in my career, having an ever-growing group of friends this past year alone and now facing the reality of being a new uncle, feels like getting a gift you had just aged out of but still appreciating the thought that’s there. I’ll most likely be playing Arcade mode still, and as soon as I get that beatmap editor I’ll be making the New York Indie Rock scene every other person’s problem in the leaderboards. One of the final passages in the credits is from lead programmer Reyah Koehler, saying

thank you so much for seeing this game to the end. we all worked really hard on the game. i hope you loved or hated it, and enough so that something about it sticks with you for a while. Thank you for believing in us and giving us the opportunity to try and make something special for you.

There’s a lot to love about UNBEATABLE, there’s a lot I’ve learned to hate. The game has a beautiful soundtrack, the rhythm sections in story mode will just be skipped over if you fail them. The character designs are fun to see, the other minigames in the narrative are clunky and don’t feel as engaging as the core rhythm game despite the artistic direction. I’ll probably be thinking about this game for a while, and to those of the team who read this I will still probably dap you up when I see you at Magfest and highlight the things I did enjoy. I think that’s what sticks the most at the end. Stories about losing your way feel different once you’ve finally started to get a handle on things, FLCL becoming less this revelation of everything I thought was true and more a fun nostalgic look at when small things mattered so much. They’re precious because of the flaws. For now, I am a little heartbroken as I collect these thoughts that feel so different to the preview I beamed about in 2021. It’ll heal, and luckily I’ve got a great soundtrack for that healing.

"I know you'll love it, I just know I didn't"

On one hand, you have a great rhythm game that's made by fans of the genre eager to get new players into the scene. On the other hand, there's a story of rebellion that's muddled by uncertainty of where to drive the car. It's a skeleton that I thought I'd love going in, but ended up leaving me with a lot more frustration by the end. Please try this game on your own though, as it's still worth experiencing firsthand.