This article contains references to Self-Harm, Suicide, Mental Illness, and Trauma.

This is an essay about pain.

Writing has been difficult for me lately. Not because I lack things to say but because everything I want to talk about is weighty. To do them justice, I would have to unearth aspects of myself which are sharp or frightening. Moreover, throwing my pain into a document doesn’t automatically make my words profound.

When I started writing, not for an assignment but for the purpose of expressing myself, I made a promise: I would always be honest. Insincerity is an infestation which has plagued too many for too long. Even lies, stories about fabricated places and events, can be tools to tell the truth; the truth can be mine or of the world at large.

It should be obvious then why writing has been difficult. I want to tell the truth and yet, often for the sake of myself or the comfort of others, I lie or obscure. I talk around the abysses; I avoid plunging others unexpectedly into Hell. When people ask what my favorite childhood memory is as an icebreaker, well, better to lie than inflict needless pain.

All the same the itch remained, to tell the truth. There is no inch of my heart I would not exhume to better explain myself. People are often uncomfortable with such displays of sincerity. The training to hide the deepest parts of ourselves from everyone except family or loved ones is ingrained deeply. I go against this standard today to better articulate why I value what I do.

With surgical saws and scalpels, I cut deep and offer my own heart; for you to keep or to throw away. Either is fine.

Here are three games with pain inside.

Three Cheers for the Sick Girl

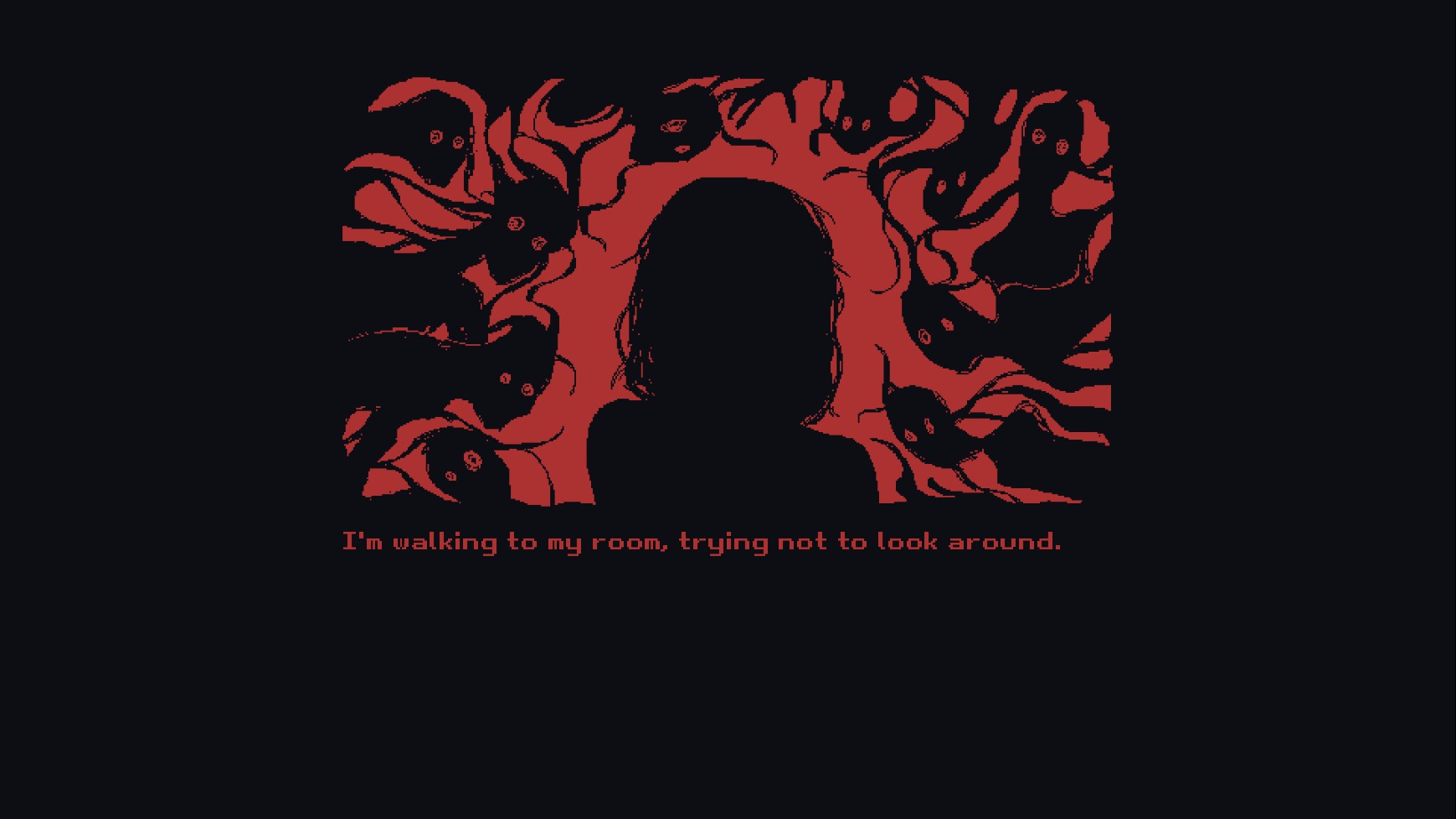

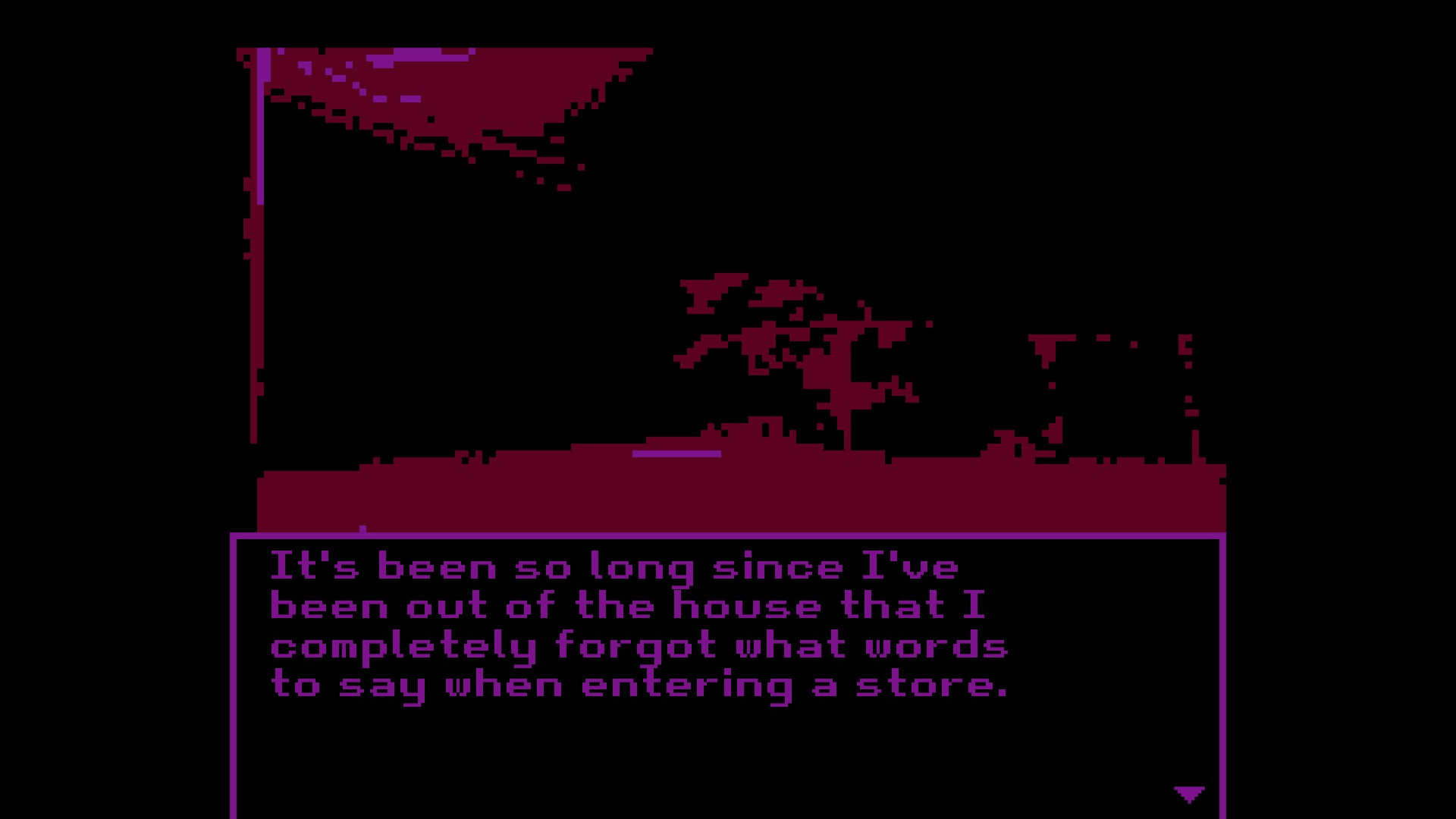

Milk Inside a Bag of Milk Inside a Bag of Milk is a 2020 visual novel created by Nikita Kryukov. First impressions are often of its eye-searing color palate and disconcerting ambience. The art is distorted and swirling, the world itself seeming to intort and destabilize. Even the voices, the chatter as words populate the text box, seem to have a quality of lucidity robbed. The soundtrack builds on this feeling, creating a tranquil yet tension-filled tone, like a steadily building pressure between your shoulder blades.

The story follows a single event, one goal: Help the unnamed girl—called Milk Girl or Milk-chan, by the community—buy milk. Simple on the surface, yet it proves anything but. The task complicates as you are forced to contend with the profound unwellness of the protagonist. She compulsively counts her own steps, speaks to voices which aren’t there—you—and seems brought to the periphery of a breakdown by simple social interactions. The world is as it appears from her own eyes; its distortions are real, to her. Fellow customers or staff in the gas station she visits appear as spectral monsters. What once appeared simple, expands into something textured. It is your goal, as a voice in her head, to keep her focused on the task at hand; hindering her quest with cruel words only causes the game to prematurely abort.

She sits with you after the trip and chats about the nature of living this life, of seeing the world with her eyes. A voice interrupts her—it is time to go home. She obeys. Before entering, she allows herself to hang from a great height, to alleviate her fear of them. Her mother waits for her inside. Her sudden intrusion causes the once space-filling music to leave the room; only vacuum remains in its absence. She interrogates the girl.

“Did you bring milk?”

“Did your new medicine help?”

Then, devoid of compassion,

“Go to bed.”

For the first time, the story is seemingly not in first person. We stare into the protagonist’s own eyes, pupils constricted like she’s staring into the sun. The game ends.

Many thousands of words have been written to identify a core theme or what the game is “about.” The protagonist herself rebuts clarity; she simply doesn’t want to talk about what is “wrong” with her. I will not make further comments or try to establish some authority about what her deal is; I will only articulate what I felt.

The profound feelings of isolation, difficulty with integrating with normalcy, voices in heads, delusions and paranoia; these are all things I’m familiar with. With so limited a cast, and the strange intimacy of staring into her thoughts, we can easily identify with the protagonist. Her pain isn’t hers alone, she asks directly for help, even as early as the title screen. We carry her burdens to the end, until we are abruptly cut from her.

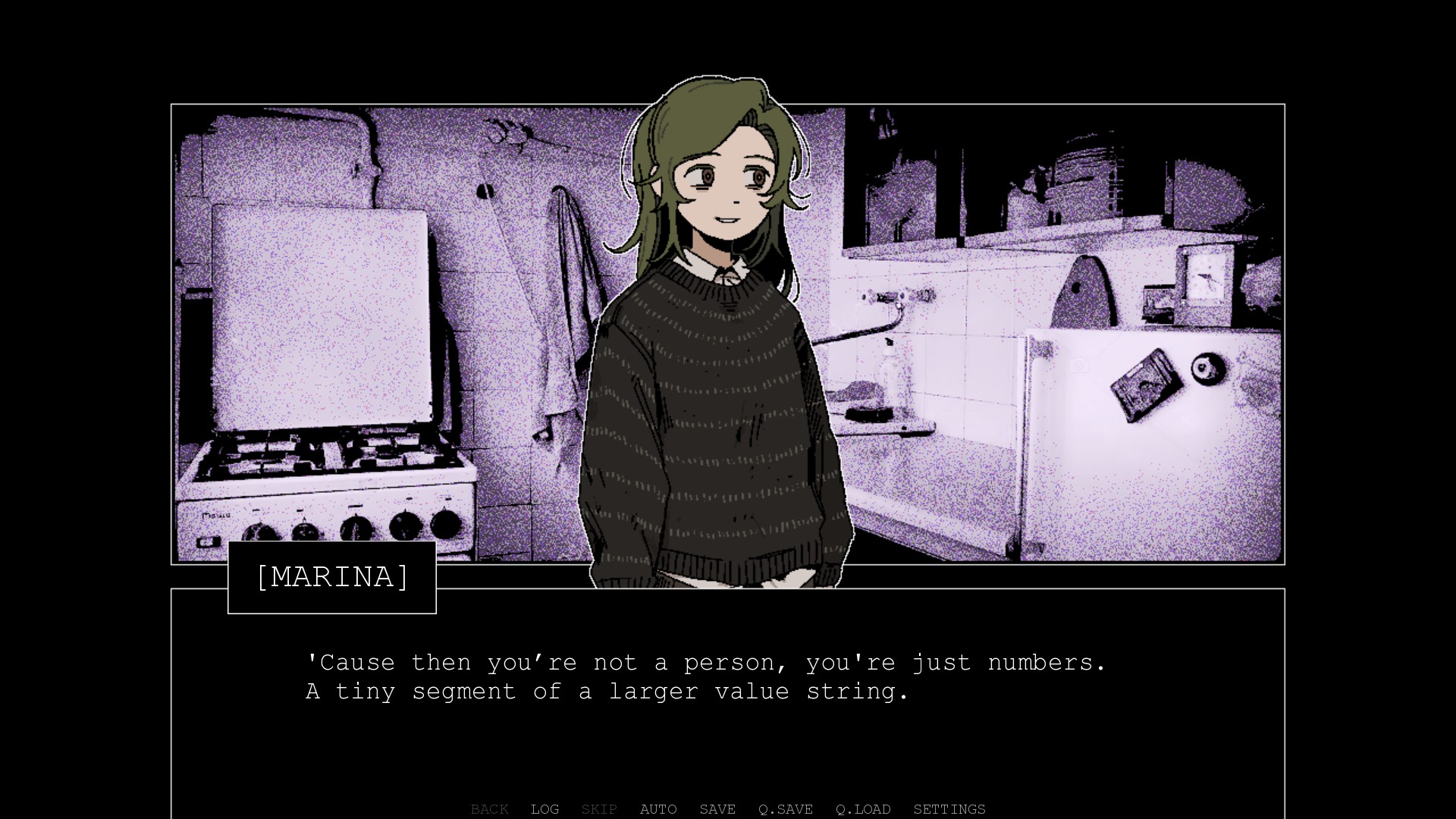

Its sequel, Milk Outside a Bag of Milk Outside a Bag of Milk, released one year later. It has a more clearly defined art style while keeping a simple, monochromatic color scheme. The music retains much of the twinkling synths of its predecessor while also incorporating almost noise-rock-like elements; electric guitars screaming oppressive notes, crushing you into a corner.

The story picks up immediately after the first. The girl enters her home only to end up in an altercation with a distorted figure. It wears the mother’s face from the prior game, yet the girl describes it only as a creature. Their engagement is less mother and daughter, and more a pet owner trying to force a dog to spit up chocolate. Grappling, a needle enters a vein; the girl vomits, then enters her bedroom. The event is violent and jarring, almost startling. It immediately diffuses into the tranquil synths of the protagonist’s room; she has no further comment.

Where the original game is an exploration of a single task, Milk Outside is an exploration of a psyche. You, once more as a voice in her head, reappear as she dumps her nightly regimen of pills into the garbage. From this point, you are given far more dialogue choices than the original game. You interrogate the protagonist’s thoughts and beliefs, occasionally steering her onto other paths. You delve further into her mind, learning about formative events through the lens of the girl’s own perspective. There is no choice but to interpret and understand while within a captive view.

Once more, I was driven to sympathy. I’ve lived a life like this.

Then, in 2025, I played Z.A.T.O // I Love the World and Everything In It by Ferry, known also as Nopanamaman on her Itch.io and Tumblr. One would initially struggle to find an immediate connection. Its art style lacks the immediate surrealism of something like the Milk games; its length is greater than both of those games combined; its events are not necessarily confined within the point of view of its protagonist. The setting is the USSR, 1986, taking place within Vorkuta-5; it is a closed city, which when translated from Russian, makes up the game’s acronym: Закрытое Административно-Территориальное Образование or, when romanized and translated, Zakrytoye Administrativno-Territorial’noye Obrazovaniye; Closed Administrative-Territorial Entity.

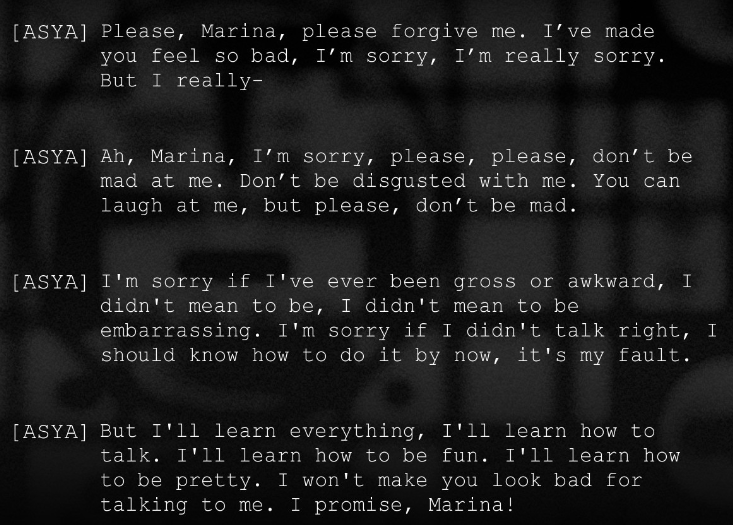

The story follows one Asya Shubina, presently enduring the traumatic experience of an acquaintance and classmate going missing. Asya, when compared to the protagonist of Milk, is a more functional character. She goes to school, and interacts with others—not well, but again, comparatively. Her specific issues seem to stem from an immense amount of self-hatred, as well as a—in some senses delusion, in some senses condition—connection to the underlying world. This is where the connections to the Milk games came unbidden.

There is an undercurrent of wrongness to Z.A.T.O.’s world, to everything in Vorkuta-5. The citizenry abide a near BITE model level of social control, a diagnostic meant for identifying cults; none enter, none leave, and if one must leave, they must deny Vorkuta-5 ever existed at all. A place of only a few thousand citizens means any discrepancy from the norm equates to social suicide. The missing classmate, like Asya, failed to integrate into the social hierarchy; resultantly, few mourn her disappearance.

Asya talks reverently, manically, about the beauty inherent to all things the world makes, as if she is speaking to the universe directly. As the story progresses, details about the world seem to jitter and distort. Asya at one point stands outside a car repair shop, gazing at the sign; its opening and closing times falsify and rewrite with every reading. Asya’s panic attacks seem to twist and distort the color of the world around her. Characters act as if afflicted with some underlying level of wrongness, until eventually, things come undone; a knot being tugged from a length of rope.

The common thread of these games, other than my sympathy for their main characters and their relatability, is of characters pained by things they cannot fully articulate; a great weight people outside their experience fail to understand. The burdens they carry isolate and estrange them. Their traumas only seem to compound into yet further traumas. The battles of mental illness, or their metaphors, are turned into visual novels for others to see, understand, and perhaps to empathize with.

Swallow the Sick Girl

When examining the communities built around such games, I find two distinct camps. There are those who—like myself—sympathize for their protagonists, feel their pain, or perhaps find them relatable. Others seem to seek out this kind of content for less wholesome reasons. Such individuals who seek out games like Milk have left others to speculate on an entire genre of this type: “I-Can-Fix-Her” type fiction, where the fantasy is finding a categorically destroyed person and raising them up, for a sense of personal gratification. People who seem excited to see a person so weird, so downtrodden, as to behave in ways they cannot understand.

“Schizo GF simulator,” says a review on Steam.

“Using the DSM-V as reference, I have diagnosed Milk-chan with the exact mental illnesses I think she has,” says a community post.

“How to not be a Schizo: take your meds,” says another, repeatedly.

More lecherous and dehumanizing things have been said, you get the idea.

When I see such words being written—genuinely or ironically—I can’t help but think of a scene from the 1980 film The Elephant Man. Joseph Merrick—called John in the film—is surrounded by an encroaching, black-garbed mob after being chased through a train station. “I am not an animal! I am a human being!” he screams. He is fiction; he is real.

The clip of the scene, commonly viewed on YouTube, accumulates millions of views. The comments fill with a sort of self-congratulatory whirlwind of directionless compassion; they talk about how the scene broke their heart, or compelled them to speak on how they would have certainly reacted differently.

It’s easy to feel compassion for a fictional character at the end of the day. They can be polished, blemishes and complexity removed, interiority erased. What remains is a person who seemingly exists to be victimized, never deserving it, but unrelentingly destroyed. It is easy to consume a victim; just as easy as congratulating yourself for not being part of the barbaric horde.

While I don’t have the physical deformities of someone like Joseph Merrick—in no way do I proclaim my struggles comparable to his—I think often of this scene. I think of smartphones when I’m out in public. I could have the singular worst day of my life, and someone, bemused, could capture it. My pain would be posted online, without context, for millions to see, as sustenance for their digital appetite. The online freak cage expanding to contain all of reality in sick entitlement.

Here lies my point: it is easy for an outsider to gaze at your misery and derive moral dessert from it while also failing to see anything resembling humanity.

“I feel compassion for this sad, wretched, broken thing,” they say, while having no compulsion to treat real people with compassion.

They feel bad, in the way one could feel bad seeing a cat carcass on the side of the road, having failed to cross the street. The extension of empathy to a theoretical pain which does not share a common orbit with me. Games, like all fiction, have an in-built disengage mechanism; you can turn the game off at any point and walk away. When the emotions grow too large, or the character annoys you, you are free to jettison them from your concern. Yet, in real life, the dead cat on the side of the road remains, even after you stop caring about it.

Trauma victims in fiction often fall into such archetypes. The quietly sad; those broken, who don’t realize the profundity of their brokenness; the heart in agony, which yearns to smile anyway. But what of those who aren’t appealingly broken? What about those who are messy and sick and angry and not immediately pleasant to deal with? What about the victims who aren’t easily swallowed as commodities to allow you to feel good about yourself?

To the people who engage with such stories, for such reasons, I would be lying to say I did not hold contempt. While I don’t believe every example given previously contained genuine malice, it informs an internal rhetoric. People “like this” are commodities to be devoured. People want to believe mental illnesses are “normalized.” I can assure you most assiduously they are not. People have told me my mental instabilities make me more attractive, interesting. I tell you now if you are confused: fetishization is not the same thing as being “accepted.”

Unbidden, at my worst moments, a thought comes to my mind.

“These mental problems aren’t going to be ‘attractive’ for much longer.” I am no longer a mute, dead-eyed girl with cuts on her forearms; I’m a woman grown with scars like lightning, a mean tongue, and unattractive fucking problems.

Once you reach a certain age, the world passively or actively starts believing it’s about time for you to get your shit together. You aren’t a sad little kid, getting freed from their abuse in a court room to perversely watch on YouTube; the interest seems to lapse there.

I sit here, writing this, today and for all time, disabled by the broken pieces of me. There is no shit to get together; my feelings, or a stranger’s, have no say in the matter. I hate myself for it every single day, even if it isn’t my fault.

So, all I can do is hope. I hope compassion can grow in the hearts of some; true compassion, for the real people these stories are meant to depict.

In the Mirror, the Sick Girl

This, is the most frightening part. The part where I come into danger of being too scared to write anymore. I sweat. I cried several times simply committing it to text. But I made a promise.

Now I answer the question, implied by writing this at all: what do I get out of these stories? Why do I repeatedly play games with protagonists who are demeaned, hurt, ruined people?

If it wasn’t obvious, I will answer bluntly: I, too, am of their ilk.

When I first engaged with these stories, I was captivated by the pain, so similar to my own. It wasn’t just meaningless suffering; any story can show you scenes of grief and anguish. These were splinters of myself I found in these stories. Characters struggling with dissociation, trauma, compartmentalized psyches, things forgotten or repressed, psychosis, paranoia; I am intimately familiar with every single splinter.

Many stories are not made for people like me to empathize with or help others to understand our pains. They are made about us, not for us. Our problems are called insanity. People like me are called crazy; the word psychotic is used as a general catch-all for “whatever actions or behaviors of others I do not care to understand.” Games often write scenarios where the mentally ill, in places meant for therapy and healing, are shown to be bloody, deranged inmates, kept from the good citizens by a single layer of cinder blocks; the game, just as often, will do contortions to justify their summary executions.

Obviously, this is not unique to video games. There are dozens of works which dehumanize or estrange “the other.” These impact the opinions of people, of policy, on real living people. It is difficult to fight against, especially when the language to articulate your own experiences is gatekept or obscured. I have overheard conversations—in public no less—where people confidently demand people with my sort of conditions should be put down, or “put against the wall” for the safety of “normal” people. I have been asked by supposed professionals if my condition functioned like the works of pop-culture. Therapists and social workers have told me an official diagnosis would be a financial death sentence; a single ICD-10 code would preclude me from ever holding a job again. Imagine! Something so terrible!

What is unique, and what I think lives in the games mentioned in this article, is compassion. Maybe intentional, maybe not, maybe even imagined. Yet, in my worst moments, it was like a mirror.

The mirror whispered, “I see you; someone else knows you; even in pieces you still exist.”

Yet, in extremes this too is a sickness.

When I first found these stories, their value was this: if the whole world hates you, if it has consistently victimized, destroyed, and alienated you, you are allowed the option to identify with your own victimhood. It is easy to tell yourself; you are simply a natural-born victim; circumstance has never been on your side, so find shelter in your own broken bones.

“I am broken. That’s just how it is.”

I found these stories when I was still coming to grips with my fragments. I ran away from a living situation which permanently damaged my body, my mind, and my soul. It has been ten years since.

Before then, I considered myself a normal, if depressed, person. I laughed; I smiled. Ignore the fact I cry if someone moves toward me with a little too much intent. Ignore the fact I sometimes freeze, staring into nothing, fingers twitching like spiders twisting silk. Ignore the things I feel and hear and see and say in my worst moments.

No, something was clearly wrong.

As I grew, away from the horrible place, I realized how much of me was missing or broken. In a therapy appointment in 2019, I was asked when certain problems had begun to manifest. I didn’t know. My therapist took another tact; she asked me about a small part of my childhood. I didn’t know. She asked me a question I did not expect to cut me open.

“What is the earliest thing you can remember?”

My mind swam. Surely there was something? The pain was real, right? I knew this pain; exhaustive was the pain. How were memories of it so hard to find?

I realized, in a neutral-colored room filled with stim-toy tchotchke, my memory effectively began in 2014. All else was obliviated. The session ended as my therapist realized I was, in fact, not a case some slight suggestion to be happier could fix.

I don’t remember driving home. My apartment door admitted me as usual, though, looking down at my own hands, I realized my own blood was dried under my fingernails. A roommate greeted me, half awake, then noticed the self-inflicted lacerations I did not remember placing.

“Not going to work again, I see.”

“Go fuck yourself,” I said. I cried. A breakdown at the implications of my own brokenness, of my unreliability.

“I can’t deal with this.”

I was left alone in the room. As predicted, I called out of work, inputting numbers with fingers still sticky, forced to still a shaking voice. I created an air of professionalism as I told them, once more, I was a failure. The transaction concluded, I collapsed to the floor.

Surely, I was the lowest thing in the world, I felt. Surely, nothing is as wretched as I?

Milk Inside a Bag of Milk Inside a Bag of Milk released as I abandoned any semblance of normalcy. I had stopped working all together. The room containing my computer was a cocoon. The only places I visited were the bathroom across the hall where I vomited my guts up when the heat of the room became too intense and the kitchen where I found trash to fill them again. Time passed without me. Sleep when the sun was up; sleep when the sun was down; it made no difference. I found the game contained in some video-essay or another, binged in lockdown.

I played it. Over and over again, I played it. I had never experienced anything like it. This image of myself monogrammed to a screen. This broken, pathetic thing trying and failing to do a simple task. The simplest thing, buy some milk, expanded into an ordeal taking hours and causing extremity-numbing pain; I could relate. Finally, there was someone in the same pit as me. It didn’t matter if she wasn’t real, or if the story made my heart hurt. Someone, somewhere on earth, knew me.

I drove to an intensive outpatient therapy program recommended by a therapist who would, in a few short months, tell me it would be better if we concluded our professional relationship. The intake nurse recoiled in fear when I told her what was wrong with me. She told me my problems were too serious to expose the other patients to; my trauma was too traumatic. I had to, she demanded, prove to her I was not a danger to myself or others, or else she would be forced to institutionalize me. Imprisonment would be worse. I performed the demeaning social transaction demanded of me.

“I am safe, there is nothing to be afraid of.”

Sorry to bother you. Sorry to bother you. Sorry to bother you.

Life continued to get worse when Milk’s sequel was released the following year. I sublimated more into this identification with my own victimhood. I rotted endlessly. Weeks passed in eye-blinks. I turned into a monster so addicted to pain; it became my only defining character trait.

I could continue, probably indefinitely, but I think you understand.

Why do I vomit up my pain like an owl pellet for strangers to pick and pull the bones from like a high-school biology class? Just as people can consciously or unconsciously dump “the Trauma Girl” into a freak cage to ogle at, so too could I. I did it to myself. It was miserable. I estranged others with my own indulgence in my bullshit. I spoke unfiltered in inappropriate spaces about the most jagged, bloodied pieces of myself.

Better to filter them out before they can abandon you. Better to lose yourself in your pain rather than pretending it didn’t exist. Better lying in my rot than dragging myself one more fucking excruciating inch.

Behaving in such a way, I brought myself to the precipice of oblivion. It was only the intervention of more than a dozen incredibly caring, incredibly compassionate people which saved me. I would not wish such things on the most hateful person I can imagine; not even Counter-Strike players deserve such things.

Yet as miserable as it was, the experience wasn’t valueless.

More than anything, it showed me the value of finding the pieces of myself in other things. When you fail to articulate a problem, when there are no words, you suffer. You grapple with a problem the very concept of language itself asserts isn’t a problem. To find characters whose pain is similar to your own, is to see yourself, and to empathize with the other; it is to allow yourself in turn to be empathized with. More, finding characters in such suffering allows you to find the ones who persist past the pain. Even at a young age, an age I cannot remember easily, I was hunting for something, anything which reflected me. So many of the stories I gravitated to easily as a child, I learned in retrospect carried my burdens with me.

A story for another time, perhaps.

Today, I carry so many stories telling me yes, the pain is with you, but it too can be walked with. The Dark Knight Questline from Final Fantasy XIV, Pyra and Mythra from Xenoblade 2, the character of Fei Fong Wong from Xenogears; there are many more, and I hope, as the stories find their audiences, more people like me find the courage to tell their own.

With such stories, in my darkest moment, I found the truth: identifying with my own misery was not living. I wanted to live, to love, to connect with other people. I wanted to be loved, broken pieces and all.

I decided then: I wanted to get up and keep walking. So, I did. I decided to be brave then, as I am brave now. I walked face first into the dark.

Cradle the Sick Girl

Now, today in 2025, I am still broken but it is no longer my only personality trait. When I played Z.A.T.O., I found myself once more identifying with the main character. In all her self-hatred and estrangement, I found myself.

Z.A.T.O. isn’t a uniquely novel story, it isn’t earth-shattering or breaking new ground. It finds itself following the same sorts of trappings as many Denpa-Kei inspired stories of the frequencies of the universe and the people who choose to live in their own fantasies. People, like me, will identify with the themes of social estrangement and dissociation, adding Asya to their rotating cadre of trauma-girl profile pictures alongside Lain and Milk Girl. I don’t judge.

Where Z.A.T.O. differs for me is its final moments. The world is crumbling—thoughts, names, and identity are falling away. What remains is the message, the message to the universe. Nothing matters but gratitude to the universe. Asya climbs a radio tower, and as she reaches the top, there is the world but also her. The name in the title box can only refer to her as The Girl now. No one remembers their names. But they remember there was a message. A simple one. It broadcasts out loud, for all to hear for miles away, even as they cease to exist. A Morse code message of love; for the universe of course, but most importantly, for herself.

I connect these stories in my mind as the path I have taken with my own pain, my own trauma, my own sickness. I have gone past the infinite darkness, and I stand on the other side still alive.

I know I’m going to die someday; death is the fate of everything which has ever lived; but I live now to build something to make living worth it.

Before I go, I want to encode my own message, for myself, for the universe, for you. Maybe you too are like me, carrying some hidden darkness the world has left you, leaving you feeling broken and empty. These words are too raw for any lingua franca, too frightening for me to say nakedly to myself.

So, take them now, as sound, encoded to the universe and to you.