Every year I post one one of these screeds, nobody has gotten the hint that I am unwell and need help. I am crying out. Please, someone, anyone, free me from my turmoil.

10. Arc Raiders

There is a deep down pinch of regret putting this on my list of the best games of 2025. I regret putting it here because there are many aspects of how Embark Studios uses generative AI that I find deplorable and detract from the quality of the game. This may surprise you, but there are some aspects of how they’ve used deep learning that I think are actually unique and a breath of fresh air. As much as I want to get into that and cover the topic with more nuance, I desperately want to avoid doing the thing I tend to do every year where I go “I love this game, but” and list off a bunch of negatives that may come across as outweighing its positives. In most, if not all of these cases, it’s usually because a game does something extremely unique that you won’t find in similar games of their genre.

What I find truly unique about Arc Raiders is that it’s a masterclass in creating a space that sets you at unease. Sure, sometimes the way the loading screen tips explain player interactions can be heavy-handed, but they’re not wrong. Seeing another player often means keeping your guard up. You might hear gunfire off in the distance and it immediately sets you off, even though you know rationally that it’s, more likely than anything else, a player shooting at one of the robots instead of at another player. But that’s not the point. With small moments like that, distrust has already been sown and, even if you have pure intentions, your finger is still on the trigger ready for something to go down. I’m usually friendly to most people, but there are the occasional moments where the darkness sets in. I’ll see a team in distress, recovering from a bad robot attack or trapped in a corner with no way to escape and tell my homies “we gotta kill these guys” simply because their loot would be better if it was my loot instead.

But I’ve also had beautiful moments as well. In a game I queued into solo to bang out a quick quest, two other people also showed up at the quest’s location. Instead of it turning into a bloodbath, we all said we were friendly and just needed to do this quest. Then, another person showed up, and another person, and another. A non-insubstantial amount of people on that server all showed up just to do one fetch quest, and we all did it happily together. We all looked around for the hidden items we needed to find, and as soon as someone found it, they called it out and pointed everyone else to it. Once the quest was said and done, we all went our separate ways to do a little bit of looting before closing out the round. After grabbing a few things, I headed to the nearest elevator to return home to Speranza and what do I see but a couple of my homies from the scrapyard where we found what we were all looking for together. In that moment, what we were looking for was not some piece of old technology or an audio log or something, but it was peace on Earth. That we can put down the guns and all come together. You can find hope in hopeless places, but only if you’re looking for it.

9. Split Fiction

This section spoils ending details from Split Fiction as well as Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons.

Ok, ok, ok. I’m not gonna say “I love this game, but.” Actually, I hate this game… But. You gotta see this shit.

The third in the trilogy of Josef Fares’ whacky co-op adventures focuses on two girl writers who have gone unpublished, and who both sign-up for a tech mogul’s AI powered machine that will extract all their ideas from them. Through a whacky series of events, they get put in the same pod together and need to live out each other’s stories together. The problem? One of them is a sci-fi writer and the other writes only fantasy!!! How could they be any more different and, more importantly as the lesbians in my chat pointed out over and over again, when are they gonna kiss???

Spoilers for Split Fiction, they do not kiss. I’m sorry. They don’t kiss. I’m sorry. The upside is that if Josef Fares is as open to the critique of his games that I think he is, then his next game is going to be openly homoerotic unabashedly. He’s an ally, after all. I have to believe.

Split Fiction coming from the lineage of A Way Out and It Takes Two is very interesting to me. Neither of them are particularly well written, and if Brothers: A Tale Of Two Sons had any understandable dialogue in it at all, it might be a much weaker game for it. A Way Out, though, is ambitious. It’s straightforward, punching way above its depth, and has a bunch of extremely funny juxtaposition in the way you’re supposed to take this crime drama deadly seriously while you and your friend are just playing Legally Distinct Connect 4 with each other. Brothers was similarly serious-yet-goofy at times, but moments of levity help underscore the ultimate tragedy of the journey the titular brothers are going through. It Takes Two is remarkably goofy in presentation but is underscored by the darkness of a family going through a divorce and a child who doesn’t really know what’s going on. With Split Fiction, the real-world stakes are so cartoonishly stupid that they don’t feel particularly different from what the characters are going through while they explore each other’s worlds.

The narrative gimmick of Split Fiction is that each of the worlds the deuteragonists Mio and Zoe go through are all stories that they’ve written in the past, but, more importantly, each story is based off of a real world event that shaped them. Both characters are all too eager to point this out, too. Zoe is unabashedly straightforward about it, often stating that “this story was based on a time me and my sister went into the woods” or something similar. Mio is more withholding, but it is stunningly obvious when you fight a big boss that’s an analogue for Parking Tickets, which of course plays into her overall stress of dealing with remarkable amounts of debt that she took on when SPOILERS. The other thing about this style of writing is that Mio and Zoe are just not very good writers. The game is ultimately a celebration about writing and creativity, and yet remarkably it tells so much on Josef Fares’ style as a writer. He has said as much too, talking about how the core moment of Brothers, where one of the brothers dies, is based off of his own experience as a child burying his newborn brother during the Lebanese Civil War. Drawing from personal experiences is a powerful way to write, but Split Fiction posits this idea that it is basically the only form of inspiration.

Mio and Zoe, by the end of Split Fiction, are still a sci-fi writer and a fantasy writer. Their experience sharing the stage with each other, exploring each other’s works and growing deeper together as people, doesn’t seem to particularly shape how they each individually write, because the end result of their experiences together is that they co-author a book. In fact, they co-author a book based on their experience in the idea stealing machine and it’s a mindbending thriller that bends into both sci-fi and fantasy genres but is, most importantly, an auto-biographical story about their journey. That’s right, they write the book Split Fiction and it’s the first book either of them ever get published. Am I joking? Is that the real ending? Who knows!!! You have to play it for yourself!!!

That’s all to say it actually plays really well and is a fun platformer that does some really amazing stuff with co-op presentation that is extremely cool and very unique and why I recommend this game in the first place. But unfortunately I can’t tell you about that, since I’ve spent most of this section of my list talking about something else that doesn’t matter. Will I learn from this? Let’s find out!

8. Rematch

Rematch is, put bluntly, the first sports game. You may believe that there are other sports games out there. There are games that simulate sports for sure. You can control a team and run it up a field. You can switch between players and try to dunk buckets. But none of them compare to the feeling of being on the field. You are one player, on a team, on the soccer field (with the rules bent to be more freeform than traditional futbol) and you have one goal: get the ball in the goal. And it rocks.

Jokingly yet accurately referred to as “Rocket League without cars,” Rematch feels like the first time anyone has examined the space of sports games as they, fundamentally, haven’t changed much since the Super Nintendo era, and decided to build one from the ground up that feels like you’re playing a sport. Rematch has training modes that will teach you how to play the game, but other than that, it doesn’t have a single-player mode. It’s all online multiplayer. It wants you on the field ready to get your ass handed to you by other players way beyond your skillset. There are mix-ups, team plays, special moves you may not know how to do. You may see someone do something and go “how the fuck do I do that” and then go into the training mode to lab it out until you too learn how to do it. Even when you’re doing badly, getting on the field with your team, especially with your homies who are all learning together, is intoxicating. And then once your start to form your own strategies and start to make big moves, start to score goals, start to consistently win games, there’s nothing else like it.

Rematch is the first sports game. You may believe that there are other sports games out there. They are not the same.

7. Drop Duchy

There’s beauty in the world knowing that Drop Duchy exists. That someone, in their brain, said “what if we turned Tetris into a city-builder/strategy game?” And then they went and made it and it’s fucking fun. You would think it the work of psycho long-time game developers, but it is actually the first and only game by new French developer Sleepy Mill Studio, with an in-house team of 9 people. Drop Duchy feels like it should be a massive success, and as an introductory game for a small studio, by all rights, it has been really good for them as they’ve continued to release new content well into 2026.

Drop Duchy works because of how neatly it simplifies each aspect of its inspirations. You build cities by placing pieces very similar to tetrominos. Many of those pieces have unique traits to them, and perhaps most importantly, soldiers. You need to make sure that your number of guys is higher than the number of your opponents. But wait! What’s this you might say? A triangle, based on weapons? A rock-paper-scissors style of strengths and weaknesses to every troop type that you may use to gain advantage on your opponents?

Drop Duchy starts you slow, introducing new concepts once you feel like you’ve gotten a handle on its unique style of puzzle-strategizing. There are multiple times throughout the game where I’ve gotten a new unlock and said, out loud, to myself, alone in my room at impossible hours of the night, “This changes everything.” Even the new DLC factions that have been released so far seem based on the same principle of “oh you this thing that’s fundamental to how the game is played? What if it wasn’t like that?” And it still works! It starts simple in order to complicate itself with new things that are unique to Drop Duchy, adding more complication once you might be thinking you have your head wrapped around everything it has to offer at such a comfortable pace. Drop Duchy is awesome. More games should be “what if we made Tetris into something else?”

6: Pokemon Legends: Z-A

This game had a remarkable challenge, perhaps an impossible one. Pokemon Legends: Z-A comes as a successor to Pokemon Legends: Arceus, which is, in my humble opinion, the best Pokemon game ever made. Or, to be less hyperbolic, the first time a Pokemon game has felt original in decades. Pokemon Legends: Z-A put a big focus on catching Pokemon, what that means from a gameplay perspective and how it’s gone stagnant over generation upon generation of Pokemon games. It came up with the beautifully simple yet elegant system of, in real time, picking up a pokeball and throwing it at a Pokemon. Outstanding. Remarkable. Simply divine. For a series this long-tenured to redefine its core mechanics in such a simple yet satisfying way. How in the world could Pokemon Legends: Z-A, a game that in structure looks like the exact opposite of Legends: Arceus, follow in large, Snorlaxian footsteps?

Pokemon Legends: Z-A takes upon itself a similar challenge. If Legends: Arceus’ gameplay thesis was on how to redefine and remake catching Pokemon from the ground up, to turn it into something realtime and simple and fun to do, Legends: Z-A’s thesis would be on battling. It would take the long-tenured and sometimes bemoaned battling of Pokemon and turn it into something fast paced, real time, and fun. You can argue that Legends: Z-A’s take on battling is not as elegant as the turn-based style that Pokemon has been synonymous with for generations, and frankly I think it would do the series a disservice to drop turn-based battling entirely, but battles in Legends: Z-A are very very fun.

If it was simply a fest to mash out your strongest attacks to OHKO your opponent’s Pokemon as fast as possible, it would be a failure. Instead, Legends: Z-A opts to make you consider your plays, when you use them, what moves you can give your Pokemon in its limited 4 move set to counter other moves, what moves you pull from its broader movepool to take on certain opponents, and most importantly, how to combat type disadvantage on the fly. When someone swaps in a Pokemon that is extremely strong against your type, you are suddenly on the backfoot and need to come up with a strategy fast. You can swap out, but then swapping another Pokemon in is on a timer, meaning that if you make the wrong choice, you suffer big time. You can Mega-Evolve your Pokemon, giving them boosted stats and sometimes changing their typing, but even that’s not an assured victory against a type disadvantage.

My skills as a trainer and a battler feel like they’re being pushed to the limit in Legends: Z-A’s toughest battles. I’ve had many competitive matches where I’ve nearly run out the clock sitting on a decision trying to make sure I make the right one, or at least the one my opponent won’t see coming. I don’t have that luxury in Legends: Z-A. Even when you lose a Pokemon and get a brief break to swap in a new one, the timer to do so moves fast, and you have to go now. Time is a luxury you do not have. Sometimes it feels so fast that it’s pure chaos. It’s up to you to see if you can keep up with it.

5. Elden Ring Nightreign

I know, I know, Fromsoft game on Scott’s list, of course it happened again. There’s no stopping it. I don’t think I could leave one off if I tried. Nightreign is good, though. I like Nightreign a lot even if it is just a multiplayer side-game. I like that Nightreign is weird and has a ton of idiosyncrasies that are unique even for Souls games. Hey, wait a minute. That’s the same reason I like Dark Souls 2. That’s strange. Huh.

I’ve definitely struggled to figure out what to write about Nightreign that hasn’t been said anywhere else. So, in lieu of just stating all the ways in which a weird Fortnite-style third person action game that is clearly a budget title – allegedly initially pitched as an “Elden Ring Mobile Game” by Tencent until Fromsoft, as the holders of the Elden Ring IP (who happen to be very precious about the games put out under their banner), took over the project and retooled it into a strange multiplayer amalgamation of a ton of different influences using the signature style of combat that From has used for 15 years now that, by all accounts, should not work but does, in fact, work extremely well, I’d like to talk about maps.

Elden Ring Nightreign, unlike similar games of the same genre, up until the release of the Forsaken Hollows DLC, had one map. The map had multiple permutations, dubbed as Shifting Earth events, which would dramatically change a portion of the map and add extra optional objectives that you can engage with if you so desire during your run. Comparatively, PUBG: Battlegrounds has many maps that it has tweaked and modified over the years. Erangel, its first and signature map, recently got a remixed variant called Erangel: Subzero that adds a ton of winter-themed events that happen over the course of a game. Fortnite has an ever-evolving map that, over the course of a season, will take out and add in new areas. When a season is over, they’ll often scrap the map entirely and bring in a new one. This left players with so much nostalgia for older content that they introduced OG mode, which has been going through a selection of slightly remixed and reworked older maps from a much simpler period of Fortnite’s life.

Fromsoft has a storied lineage with geography in their games as well. Dark Souls’ interconnected and deeply vertical map, placing all the different areas adjacent to each other in unique ways, is often lauded as one of the game’s greatest achievements. Coming out in 2011, it felt unique compared to other games at the time, while also being more of a modern take on Metroidvania style world design than even its Metroid and Castlevania contemporaries. This was also the beginning of an era in gaming that I will refer to as Peak Open World. Sleeping Dogs, Shadow of Mordor, GTA V, The Witcher 3, the myriad of Assassin’s Creed games, hell, even Fallout: New Vegas came out one year before Dark Souls. Peak Open World was capped off by Breath Of The Wild, a game that tried to take an already well established genre and twist its conventions to make it more about exploration and discovery. From this point on, you start to hear the term “open world fatigue” whenever another AAA open world release reared its head.

By the time Elden Ring rolled around in 2022, its open-yet-linear style of world design was divisive among its playerbase. I am a noted liker of its world design, how it encourages exploration and leads you to incredible and unique discoveries. Many people lamented that this would be the style of Souls game that Fromsoft put out in the future, missing the interconnected worlds with very tightly constructed levels that made them so fun in the first place. Big, open, massive maps that you can’t possibly explore every inch of and, by design, have many inches which would be utterly pointless to explore, are an understandable turnoff to many people. Elden Ring’s world is by no means sparse, but there is a lot of space when you run from one place to another, especially when you’re not doing it on your horse. This meant co-op play out in the big open world was a lot of downtime and slow travel since you can’t use your horse in online play. To anyone who spends any amount of time walking around The Lands Between, it can make you feel small and insignificant.

In Nightreign, every player now has a super sprint that you use to travel from one place to another in a map roughly as large as Limgrave, Elden Ring’s opening area. Nightreign feels like the exact opposite of the loneliness Elden Ring can engender. Instead of slowly wandering around with a lot of downtime, you’re sprinting from one area to another in a frenzied rush. Elden Ring almost forces you to take your time and sit and consider your options. Nightreign tells you there’s no time and you need to move move move. You have to GO. You have to go NOW. If you don’t sprint and run around and kill as many things as possible or plan poorly and kill the wrong things or try to tackle something while underleveled and waste valuable time, you’re playing Nightreign wrong. Nightreign wants you to go so fast that I never noticed that on the second day, there are literal giants walking towards The Lands Between coming from the ocean.

The breakneck pace of Nightreign, however, doesn’t invalidate exploration. If anything, Nightreign’s high-level play involves being able to look at your map and plotting out a route through dangerous territory at a moment’s notice. Fortnite and PUBG’s route planning, by comparison, gives you plenty of time to sit and consider your dwindling options and discuss them with your team, and often simply involves just heading to the next closest place in the circle. With Nightreign, you’re often picking a place based on its future value and potential placement inside the circle before it closes in and then plotting your next few moves after that. The churches where you get much needed health flasks may be spread out and inconvenient to your path compared to the places where you might want to get loot. The places you can go are always changing, but the geography is always the same. Even Shifting Earth events take up a large space of the map and are static, so you find yourself getting familiar with their unique geography as well.

It’s interesting, then, to compare and contrast these styles. Nightreign’s map is called Limveld, deliberately evoking Elden Ring’s Limgrave. Limveld is aesthetically very similar to Limgrave, sometimes feeling like parts of it were wholesale ripped right out of Elden Ring. But it still teaches you to appreciate its landscape, to know where you can successfully climb up a wall compared to where it would be a fool’s errand. It teaches you its fastest routes through repetition, and gives you the tools to move through it’s landscape as flawlessly as if you lived there. Each Nightreign’s unique characters all has a background, all comes from a distinct place in the world, and all of them feel as though they belong.

In Elden Ring, you can choose a background for your character that are all distinct to The Lands Between, but your character is always Tarnished. You can sit for hours in the vast, impressive landscapes of Limgrave overlooking the Mistwood, on a cliff in Liurnia above its massive ankle-deep lake, or on the Mountaintop of the Giants where the giant forge threatens to one day burn the massive golden tree that you can see from anywhere in The Lands Between. But you’re always reminded of the dead, that you exist in a world barely hanging on that is crying out for someone, anyone, to take Marika’s hammer. Even in your quest to become the next Elden Lord, you never feel as though you are part of this world. You are alien. You can choose a background from your character during creation that does not even come from The Lands Between, such as the Reedlander or the Seafarer. The Aristocrat’s background only seeks to “claim noble blood in the Lands Between” with the implication that they may not even be from there. You arose from a coffin after Godfrey sailed away from that place, forever taking away the grace of gold from your eyes. Your only home is the Roundtable Hold, a place where you are at first branded as a “houseguest” by Sir Gideon, and over the course of the game, you see all it’s inhabitants dwindle and leave until you are alone and the hold is burning down.

The Roundtable Hold also serves as the hub area in Nightreign, or some form of it, likely in the same liminal space it existed in during the events of Elden Ring. It’s much older now, and in disrepair, but now it serves as the base of the Nightfarers holding off the encroaching darkness threatening to subsume what’s left of this world. When you choose what character you want to play as, the other ones hang out around the hold. It is their home, fashioned with beds and desks with books and even a kitchen hall where everyone eats. During each character’s personal quests (dubbed remembrances), you see how all of their relationships intertwine and how, even in their impossible situation, they’re still treating each other as people. Some are deeply kind like the Recluse’s motherliness towards the Revenant. Others are tragic like Wylder’s resignation to never lose his sister, the Duchess. Others are dark like the Ironeye’s betrayal towards the Nightfarers as escaping his duties as an Assassin outweighs his desire to stop the night.

These people all live in the ruins of what was left behind. Like Nightreign was built on the existing world, the existing assets of Elden Ring, the Nightfarers exist and Limveld exists because the Roundtable Hold and Limgrave did. You can’t find the Roundtable Hold on a map. Not in Nightreign at least. You can find some version of it in Elden Ring, sitting inconspicuously in the golden city of Lyendell. But even by then, it is old and abandoned, occupied only by a few stragglers just looking for a place they can set a fire and sleep in a bed. But it is not your home. It won’t be anyone’s home, really. Not until everything around it turns to ash. In the closing moments of Nightreign during the game’s ending, you see sprites floating around, traversing the halls of the Roundtable Hold as it is abandoned once more. The Nightfarers, having fulfilled their duty, are no longer needed. Yet the Hold remains. Perhaps to one day become home to someone else, someday. Someplace, somewhen, somewhere, somehow. You can always go back to the Roundtable Hold.

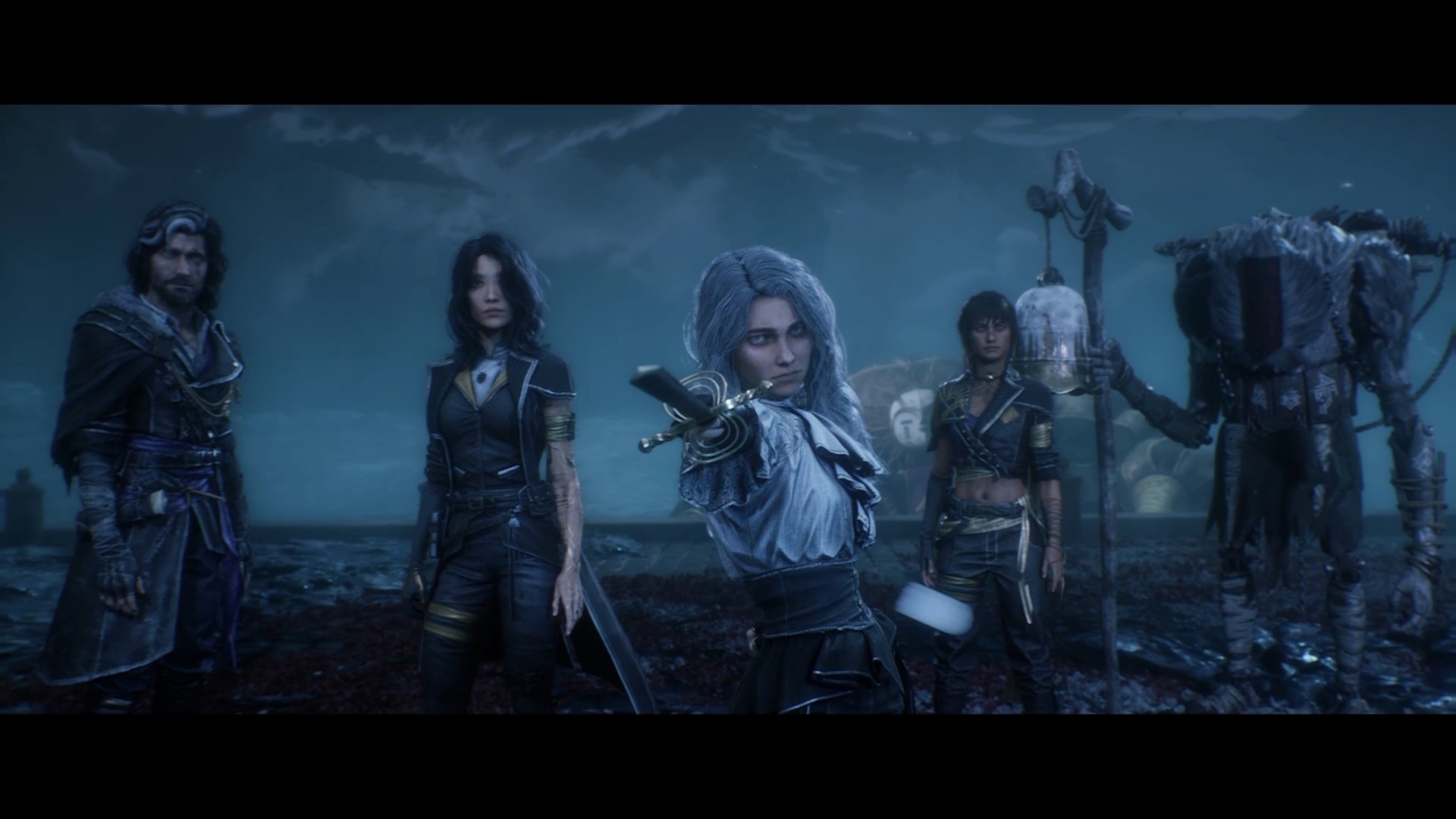

4. Final Fantasy Tactics: The Ivalice Chronicles

They did it again, folks. They remade my favorite game of all time. I like it! I like The Ivalice Chronicles. There’s things I don’t like about it, namely that it excludes content from the War of the Lions version which could have acted as a really good endgame buffer and added more replayability to it. I don’t like that the lovingly animated WotL cutscenes exist in the game but aren’t actually used, and you can only watch them in the cutscene viewer. But also, I love the voice acting! I love that they added more dialogue between characters in battle! I love that they have Cloud and Aerith’s voice actors from the FF7 Remake series to play Cloud and the non-descript flower girl that shows up in his cutscenes! I love that because it’s not actually Aerith and an Ivalician version of her, it’s just her actress putting on a posh accent! Everyone is posh in Ivalice! I love that Construct-8 has the voice of a small child! It’s good! It’s really good!

I must admit to you, though. I have been looking at the Nexus mods page for The Ivalice Chronicles obsessively in hopes that someone will put out some kind of WotL content mod. Or any more new content at all, really. I have a desire to see this thing become something more than it is, even though I know they are rushing up against their limitations at record speed. Truly, the Final Fantasy Hacktics community has brushed up against hard limits of what they can and can’t mod in The Ivalice Chronicles after busting open the WotL version for PSP emulators. But I’m holding out hope. The Dark Knight and Onion Knight classes still existed in the game’s files. It just took some clever reworking to make them whole. I want to see this become the best version of FFT that has ever existed, because it’s already damn near close.

3. Death Stranding 2: On The Beach

Awesome game, great ending. As fun as the first Death Stranding. If it was simply a retread of what Death Stranding did, then I probably wouldn’t rate this so highly, but the ending is an unreal spectacle that has to be seen to be believed. I can’t talk about it without spoiling it. I’m already spoiling several other games on this list and I just need you to know that I won’t do it in this case. I have to stand firm in my resolve here. You gotta check this shit out.

2. Clair Obscur: Expedition 33

The following section fully spoils the ending and major plot details of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33.

When I initially came to Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, online opinion havers had already planted a seed in me that it’s not a game you come to for the story, you’re there for The Gameplay. You’re there for raw turn based action RPG thrills with live action parrying and quick time events and everything. The story, for whatever unique trappings it had, was likely another banal RPG story about killing god or whatever… The thing is, though, is that online opinion havers are always wrong. Explain this, smart guys: if the story of Expedition 33 is really not all that important, then how come I’ve been agonizing over the decision at its ending for months now?

Before I can discuss the ending of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, there is a lot of ground I need to cover. I’ll try to skip over most of the story details but there are a lot of specific ones that need to be mentioned. Ok, so, broad strokes: the world of Expedition 33 takes place inside of a painting that exists in the real world, in Paris, France likely in the late 19th century, early 20th century, painted by the only son of the Dessendre family. The Dessendres are an esteemed family of Painters that have the ability to craft pocket-dimensions out of the paintings they create, at a nebulous and loosely explained cost of their life-force. What is made clear is that the longer you stay in the painting, and the more you try to paint, the further your body in the real world dies.

The Dessendre family consists of five members. The patriarch of the family is Renoir, named after 19th century French impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir. He is similarly married to Aline, also named after her real world counterpart Aline Charigot, who was a dressmaker and served as a model for many of Renoir’s paintings. Their son, Verso, died in a fire set by a rival gang of creatives known as The Writers, an act that their youngest daughter, Alicia, who was also maimed irrevocably in the fire, feels personally responsible for. Their oldest daughter, Clea, becomes bitter and cruel to Alicia, reinforcing and internalizing Alicia’s guilt over her brother’s death.

In her grief, Aline dives into the world Verso painted and refuses to leave, ingratiating herself as a godlike figure known as The Paintress. After many failed attempts at getting her to leave the painting, Renoir enters it as well in order to erase it. Alicia, seeing herself as having no more worth in the real world, follows her father. However, as a novice painter who can’t control her power, she instead gets absorbed into the painting and reborn as the character Maelle without any of her past memories.

Over the course of her new life living in the city of Lumiere inside the painting, Maelle becomes a little-sister figure to Gustave, the leader of Expedition 33. You’ve likely heard this setup for the story at this point so I’ll keep it brief: Expedition 33, like the many Expeditions before it, sets off to destroy the paintress to stop the Gommage, a yearly event that kills all of the oldest people in the world based on their age. Maelle joins the expedition as well with a feeling that she doesn’t quite belong in Lumiere. Upon setting off, Expedition 33 is decimated by Renoir. The fledging remnants of Expedition 33 in Gustave, Maelle, Lune and Sciel all reunite and attempt to continue the journey to the Paintress.

Gustave and Maelle are deeply attached to each other. When Maelle feels like she has nobody else in the world, like she’s completely alone and isolated, she still has Gustave, the one remaining thread of security for her. Which is why it’s so heartbreaking when Renoir murders Gustave at the end of the game’s first act. Jumping in to save Maelle before Renoir strikes her down, too, is another man who seems like he’s too old to still be alive, who looks a lot like Gustave but with streaks of silver in his hair. This man is named Verso.

We find out later in the game that the Verso and Renoir that exist inside the painting are painted facsimiles of their real world counterparts. Verso joins the party as Gustave’s replacement in Final Fantasy V Gulaf-to-Krile fashion, being a similar but not entirely the same character. Verso tells Maelle that he is a pianist, a different kind of artist despite his parents’ wishes, and that he played in Lumiere back before the first expedition. Maelle makes him promise to come play again when everything is over, which Verso casually accepts.

We can find remnants of failed expeditions: audio logs, previous camps and expedition flags, and the many many petrified bodies of previous expeditioners. This world has existed for a long time and the people in it have suffered for generations now, wishing for a future that they can finally call their own. Despite losing Gustave, Maelle travels with her Lune and Sciel, while still finding beauty in the world in the whimsical Esquie and Monoco, Verso’s Gestral companion and blue mage of the team. Verso has lived so long that he and Monoco, in their conversations together, recall all of the old adventures they’ve been on and previous expeditions they’ve helped. The world these people live in is very real, even if it only exists on a canvas.

In Act 3 of the game, after all about the Dessendre family has been revealed and everything laid bare, after the painted version of Renoir and the Paintress had been defeated, expelling Aline from the painting for the time being, in one last shocking twist, everyone in the world other than Verso and Maelle are gommaged all at once. The truth of the gommage was not that every time the number went down, she was killing everyone of that age, but that Renoir was attempting to kill everyone in the painting in order to expel her from it, with the number counting down being the people left she could shield due to the painting draining her lifeforce. Verso knew all along that this would happen, and helped the expedition to expel the Paintress because he was sick of living in a world as a shadow of another person. When Verso was painted, he was painted with the memories of the real Verso. He knew all about his life. He knew about the truth of the world, and hid all of this from everyone. He was made immortal by the Paintress and no longer wants to live in this world, and, in order to save his ailing mother from her grief, is willing to erase everything. He feels ownership over the painting and it’s hard not to understand why; he is the namesake of its painter.

With this truth revealed, Maelle regains her memories, but most importantly, she takes control of her ability to paint. She can create life in this world and be its god in the same way that her family could. The real Renoir finally shows himself before Verso and Maelle. He controls all the power in the world and wants Maelle to come home now that Aline is gone from the painting. He’s not like the painted Renoir, he’s gentler and more understanding, but is firm in his belief that the painting must be destroyed in order to make his family whole again. Maelle opposes this: the painting is not only a home to so many beautiful people and things, but she also feels as though it’s now her home. She has no life outside the painting. Her body is frail and disfigured, unable to speak, and seemingly beset on all sides by people who either hate her or want her dead. In the painting, she can live what she believes to be a free and normal life, the implication being that she, too, is tempted by the limitless possibilities of the painting just like her mother. However, where Aline stayed in the painting to grieve a life she lost, Maelle wants to live a life she feels like she’s finally gained.

In contesting Renoir, Maelle uses what limited powers she can conjure to paint her party members Lune and Sciel back into existence, as well as a necromantic army of petrified expeditioners to lead a full scale attack on Lumiere and to face Renoir head to head. In the final confrontation, Sciel and Lune both approach Renoir to speak their truth, that Sciel grieves for the people of the world that they’ve lost and that Lune believes that children need to be able to grow up and be their own people outside of their parents’ influence. Renoir listens to them both, considers their words, and recognizes their humanity. But his choice doesn’t waiver. He’s willing to let these people die if it means his family can live. Maelle, in a way she was not able to do in the real world, is able to speak her truth directly to her father. She believes she has nothing in her real body. She’s tried over and over again to start over but can never live down that her brother died because of her.

With their differences irreconcilable, Expedition 33 defeats Renoir with the help of the Paintress, Aline, who enters the painting once more in order to get Renoir out. The path is clear to the heart of the painting, where Verso, before anyone else, abandons the party to jump ahead. Inside the heart is another soul trapped inside the canvas. The true painter: the trapped soul, or perhaps a remnant of a soul, of the real Verso. A literal manifestation of the adage that every artist puts a little bit of themselves in their work. He has done nothing but paint since he died years ago, and he is tired. He confides in the other Verso that he no longer wishes to paint. Verso tells him that he doesn’t need to paint anymore, and is about to run him through with his sword until he’s stopped at the last minute by Maelle.

All of this explainer of the plot sets up the moral dilemma at the end of Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 that has been haunting me since I beat it. Maelle and Verso are about to duel for the fate of the painting. You choose which person you’re going to control, similar to the ending of another game CO:Ex33 is clearly inspired by. If Maelle wins, the painting lives on. Alicia will cease to exist and she will continue to live as Maelle, keeping the painting alive at the cost of not only her own soul, but her deceased brother’s still trapped in the painting. Their grief and the grief of the entire Dessendre family is the price to pay in order to keep a world full of living, breathing people alive, no matter if it’s the “Real World” or not. If Verso wins, Maelle dies, expelling her from the painting to return to living in the world as Alicia, and erasing the painting for good. The world inside the painting will cease to be.

From a pragmatic perspective, I believe most people would choose Maelle. They’ve seen the world for what it is and to let it be erased feels like a massive loss of life. If you choose Maelle and defeat Verso, Verso pleads with Maelle not to bring him back. He doesn’t want to live anymore, he just wants to die. Once he’s defeated, Verso’s body fades off into flower pedals just like all the people you’ve witnessed die in this game have as well. We jump forward in time to Lumiere in the future. Maelle has resurrected everybody and Lumiere is a beautiful and prosperous town once more. We are reunited with Gustave and his ex-girlfriend Sophie, together once again, after she had been gommaged at the very beginning of the game.

There’s a funny feeling about the gommage. It’s tragic, but everybody knows it’s coming. Once the number turns to your age, you have a whole year to live out your life and you become prepared for death. It still hurts losing the ones you’ve lost. But you know it’s coming. I share this feeling with Maelle’s ending, as everyone files into an opera house for a concert. The perspective shifts to 4:3 and all color leaves the scene, becoming a stark black and white. The curtain rises and we see Verso at the piano. Maelle did not respect his wish. She brings him back to life to perform for her just like he promised he would. We watch him sorrowfully play until cutting back to Maelle in what can only be described as a jumpscare, half of her face covered in the same curse that plagued her mother after so much prolonged time in the painting. We were told over and over again that she would become intoxicated by it, that she’ll never grow out of childhood if she doesn’t leave the painting, and that’s exactly what happens.

If Verso wins the duel, he strikes down Maelle, expelling her from the painting and back to her life as Alicia. Esquie and Monoco are the first to confront Verso, his oldest and dearest friends, and they hug him as they are the first to disappear. Sciel, who Verso had become romantically involved with over the expedition, is the next to come in. She looks at him mournfully, but is ultimately accepting of her fate, as she too disappears. Lune is the last to arrive, and she looks disgusted with Verso. She sits on the ground and simply waits wordlessly until her time, never breaking eyes with him. She forces him, the proxy for you, the player, to sit with the choice that you’ve made. The painted Verso is the last to disappear before the soul of the real Verso stops painting altogether. We cut to the real world once more. The entire family is together once again, visiting Verso’s grave. Clea is the first to leave, with Renoir and Aline behind her. Before Alicia leaves, she sees the entire party: Gustave, Maelle, Sciel, Lune, Verso, Esquie and Monoco, all there in the distance. Their memories are still with her. Maybe one day, if she paints again, she may paint them in another world. It’s hard to say, they were never her creations to begin with, but they do mean everything to her. In this ending, Alicia has a future ahead of her, and more importantly, time to grow and space to grieve.

It’s hard for me not to draw comparisons to Ursula K LeGuin’s short story The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas. In the story, LeGuin encourages you, the reader, to imagine what you would consider paradise, the perfect place to live with dancing and frolicking and friendly people there to greet you every day. However, Omelas has a dark secret, that hidden in the city is a feeble child that lives a tortured existence, essentially alone and trapped in a closet, wallowing in its own filth and considered too dumb to even know what’s happening to it. Everyone in the town knows that he exists, and once children grow to a certain age, they’re shown the child as well and are told in no uncertain terms that they must not help it in the slightest, that “there may not even be a kind word spoken to the child.” There is no reasonable doubt for any of the citizens of Omelas, every single one understands that their majestic lives are at the expense of a tortured child.

Post-gommage Lumiere and Omelas are similar in this regard: a city of people who live in peace and harmony at the expense of continued child-suffering. In the case of Lumiere, it’s not only at the expense of the stunted growth of Maelle who’s literal lifeforce now fuels the painting, but also in the soul of the trapped Verso in the heart of the painting. Maelle, too, prolongs the painted Verso’s suffering by denying his agency and forcing him to live because she simply wants him to. Maelle doesn’t believe herself to be suffering, she is living the life she always wished she could and is surrounded by people who love her unconditionally, but we know this is a fantasy for her. Even if this world is real and worthy of existence, it still exists at the mercy of a child-god who refuses to face responsibility and adulthood. From her perspective, it’s easy to see why she would choose this life, even if it meant and even if she knew it would kill her in the end. She believes that she will ultimately be unaffected by it, that she can leave the painting whenever she wants and visit home again. But we’re not given any indication that she does, as she walks her mothers path, living in an idealized version of her own grief in a world her dead brother created.

But destroying the canvas, despite its destruction ultimately being the catalyst that does bring the family back together, isn’t a great option either. At no point does Renoir consider the Canvas to be fake. He knows it’s full of people with real thoughts and feelings and full lives. Which makes his decision to end the painting feel so callous and cold. His family means everything to him as each of their families, including Maelle’s found family, has meant everything to her. But he isn’t wrong, destroying the canvas does ultimately lead to his family being able to grieve properly and live again. The painted Verso shares this sentiment. Despite being a simulacra of his own dead self, he still sees the Paintress as his mother, and he still sees that she’s suffering for him, and can’t bear to live with it anymore. Does he not have ownership over what happens to the canvas? Is he not its rightful heir? Should he have to continue on as an immortal being that cannot die, his immortality fueled by the spirit of the person who once painted him? Is his grief not valid as well?

There’s also the matter of class to consider. Lumiere doesn’t have any sort of wealth inequality. Everyone appears to be free citizens, and since the expeditions, have been content with living peacefully until their time runs out. By the time the story starts, Lumiere’s citizens live in a state of tragic contentment. Their only way of fighting back is the expeditions, where all the 67th before them had failed. Their society, however, was created by and continues to live due to the continued suffering of a family of wealthy elites in Paris, France. It’s really not difficult to see the plight of this well off family, with how many times I walked through the halls of their ostentatious manor, and wondered to myself “why do I care about these people?” Surely, their family drama could live unabated from the world of the canvas, their meddling could be less obtrusive? The canvas could be locked away in a vault somewhere and left to live as its own pocket world? The concession that the game makes here is that Aline is so drunk with the temptation of the painting that she will find a way to enter it. She’s been forced out multiple times and she keeps coming back every time. She tells Renoir she is allowed to grieve in her own way, but the way she chooses to grieve is killing her and tearing her family apart.

As someone who lived with a parent that had substance abuse issues, this hit hard for me. Seeing the same person make the same mistakes over and over again and wanting them to stop, and they just refuse, it’s heartbreaking. Anyone who’s been through that before knows how much addiction can tear apart families and rip loved ones away from you. I didn’t have a great relationship with my stepfather. In fact, I hated him, but my mom and my sister still loved him. Any time I found needles in our basement, or he would do something extremely drastic to fuel his addiction, it was another knife in the chest. My mom one day came home to find our entire savings had been emptied. A modest $10,000, everything she’d been able to save up for years working shitty jobs, completely gone. I remember the venom in her voice when she asked him where all the money went. I’d never heard her make a noise like that before.

Aline Dessendre’s compulsions are not too dissimilar from that of impressionist painters in the early 20th century. Pablo Picasso famously hosted regular opium nights in his studio between 1904-1908, until his friend Karl-Heinz Wiegels committed suicide during a psychotic break brought on by a combination of hashish and opium. Even after he swore off opium for good, he still experimented with cocaine, alcohol, morphine, and seemingly any other substance he could get his hands on over the course of his life. Vincent Van Gogh drank excessively, with absinthe as his drink of choice, so much so that it was the subject of one of his paintings in his Still Life series. Absinthe taken in great quantities has hallucinogenic properties, and while it’s a hotly debated topic that the distinct yellow hue of many of his paintings was caused by excessive drinking (allegedly, drinking too much absinthe causes your vision to slightly more yellow), there is a consensus that absinthe was a contributing factor to Van Gogh’s declining mental state.

Maybe it’s uncouth to compare fantasy painting powers with real life drug addiction. I don’t know. I can only really speak from my own experiences. But when I heard Renoir say he’s tried and tried and tried and how nothing works, how she kept coming back, it hit me. I know what it’s like to have someone so close to me so full of grief and anger to think the only thing I can do is destroy this. Renoir doesn’t want to destroy the painting either, he says as much. Not only would he be condemning everyone to death but he also doesn’t want to lose the last piece he has of his lost son. Yet still, he’s willing to give it up to save his wife and to bring his daughter back home before she falls for the same alluring addiction as her mother.

It’s not hard for me to put myself in Renoir’s shoes in that case. It’s especially easier for me to put myself in the role of Verso, being the youngest son of my family. Seeing them fighting and feeling helpless. Wanting to do something, anything to help but knowing you’re too powerless. Feeling like it’s your fault to begin with. I know in my heart that destroying the canvas is not the way to go. You can’t condemn that many people, they need to be able to live their lives. But seeing that it’s built upon the suffering of people, both alive and dead, in a cycle of endless torment. Is that still ethical? Is it ok for a world to live if it means a lone few suffer? There are none who walk away from Lumiere. The world outside isn’t made for them. They’re trapped there just as Aline is with the memory of her son, driving herself to the only comfort she has. Those who create have the duty to create responsibly, as art can often be used as a sword as much as it is a shield or a blanket or any other creature comfort fitting of this metaphor. The artist of the canvas is already dead, and he wishes to stop painting. It’s everyone else that perverts his work to make it live on.

The real Aline Charigot never picked up a paint brush, but she did die tragically of a heart attack at the age of 56. Auguste attempted to craft a sculpture of her to live on forever, but due to his arthritis and his advanced age, being 20 years her senior, the monument was never finished and served as the basis for a bronze bust by her grave. It’s easy to see where the basis for the Renoir for the game comes from, a compulsive devotion to restore something that can never again be like it once was. The ending choice in Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 follows a motif of tragic choices, leaving the player with a final moral dilemma so deeply fraught that you question whether or not you know the right answer. I think, then, I would have liked another option. Perhaps, it might be best if the canvas was hung in a museum for everybody to see. Maybe that makes me as foolish as Auguste, believing that I know better and would like to see the beauty of the world preserved, despite the tragedy that it cannot. From my perspective, though, that’s not what matters. What matters is that it’s an ending that I would have liked.

1. Blue Prince

My #1 game of the year is Blue Prince! Thanks for reading!