2019 was a particularly tumultuous year for me. In between dealing with a gamut of personal issues too boring and sad to detail here, it also marked my continued disenfranchisement with AAA first-person shooters; many were played and subsequently abandoned before coming to any conclusion. I chose instead to bury myself in Devil May Cry 5 and Sekiro while ignoring any other releases from that year. Resultantly, when Hedon, A GZDoom based First-Person Shooter, released, it went by relatively unremarked. I was not yet as invested in the indie revival shooter movement, much less the games that inspired them. I had a dozen or more things fighting for my attention and little time to spend. Then, 2020 happened.

In lockdown with everyone else and my employability collapsing alongside my mental health, I suddenly had a lot more free time on my hands. As my sleep schedule was freely rotating with nothing to fill the sleepless hours, Hedon suddenly grew much more interesting. So, with my partner watching me over Discord, I booted up Hedon prepared to be wowed by something, anything, that could take my attention away from whatever was happening outside.

I absolutely hated Hedon. I am fairly certain that the cloud of expletives and general terrible vibes extruded from me that summer is still miasmatically haunting that three-bedroom apartment. Hedon was a complex, obtuse, altogether different experience than I wanted. I, like many people in that moment in history, wanted to be soothed — this game demanded too much from me, I rationalized to myself.

That isn’t the end of this story, however. It kept lingering, itching the back of my mind as I played other games. I tried it again in 2021; it didn’t stick. Again, I tried in 2022; no dice, hated it. Having found myself in a much better place in 2024, another attempt; abandoned again. Then, finally, in 2025, I saw it again. Having completed Hedon’s capacious 25+ hour campaign, I can now say that I am fully bought in.

What changed between then and now was mostly myself. I played many more games and had many more experiences. I went back and revisited the classics that were fundamental to the genre I loved. I “learned the language” so to speak. But moreso, I had a critical change in perspective. For quite some time, I had a passive belief that games were required to come one hundred percent to me. I could play them, sleep-walker-like, and eventually their fruits would yield to me through enough time without thought.

As I matured, I’ve realized why this is as foolish as it is. Video games, like any artistic medium, require some level of vulnerability between the game and yourself. The worst games are those carrying a passive air of inauthenticity — a detached embarrassment of themselves even as they revel in a belief of self-awareness. The same cuts both ways however; players who refuse to open themselves even a little to an art trying so hard to engage. I realized I had been one of those players. This time, I did what I hadn’t done before: I had a conversation with the game and allowed myself to change.

That change afforded me more insight into the nature of First-Person shooters. Often, it is easy to ignore their subtleties. The best shooters are ones making much with very little. The delicate interplay between the tools the player has, their opposition, and the very structure of the levels themselves. Doom, for instance, even as one of the “simplest” iterations of the genre, demonstrates how essential this coaction is. On a micro level, playing Doom well requires you to engage with the level geometry, prioritize targets, and efficiently use your ammunition and weaponry. On a macro level, you have to understand your position in the map and in the episode itself as it relates to your resource utilization, and your ability to identify and find secrets. When done well, this passes into the back of your mind — a series of intuitive decisions which generate satisfaction.

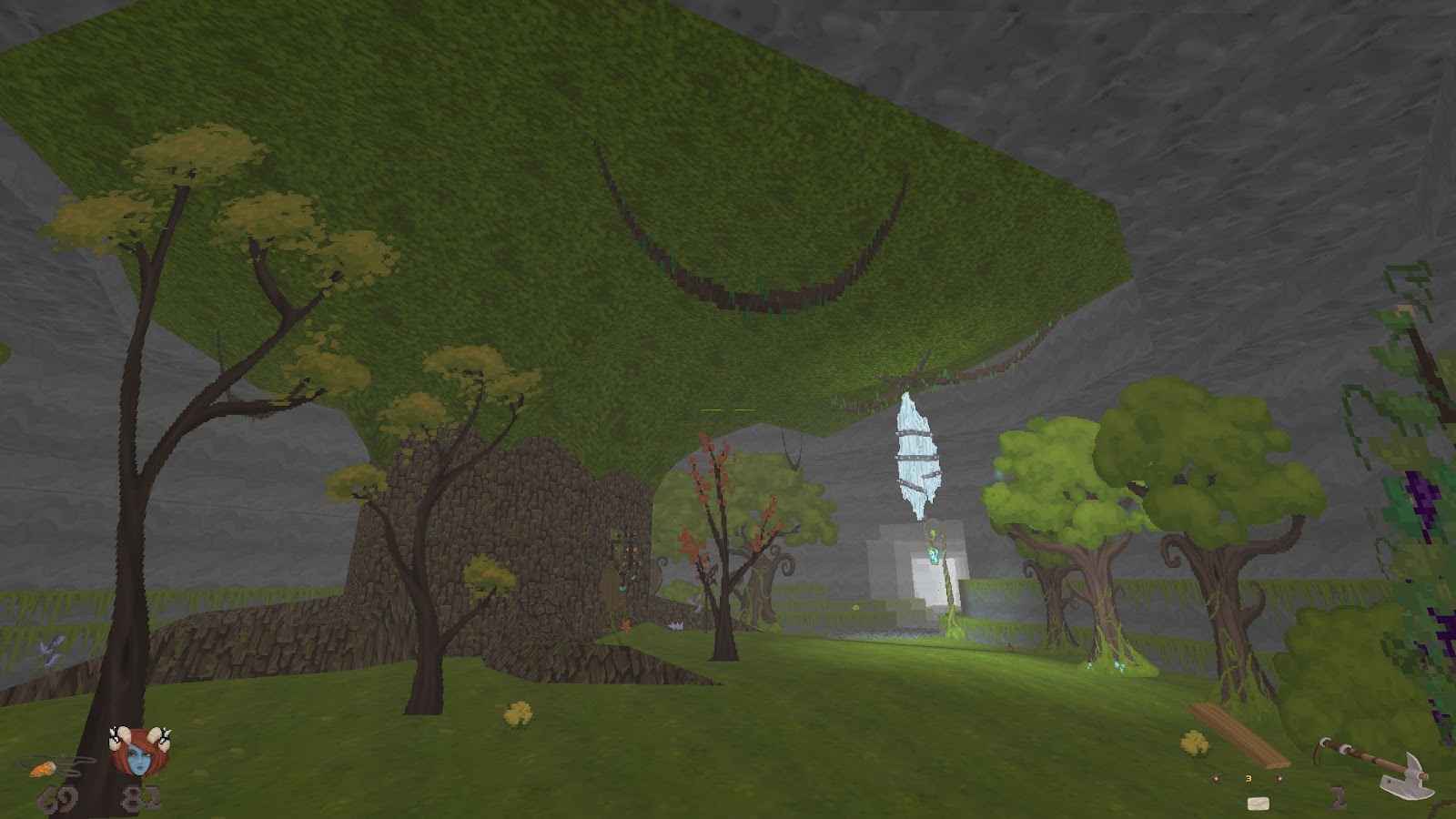

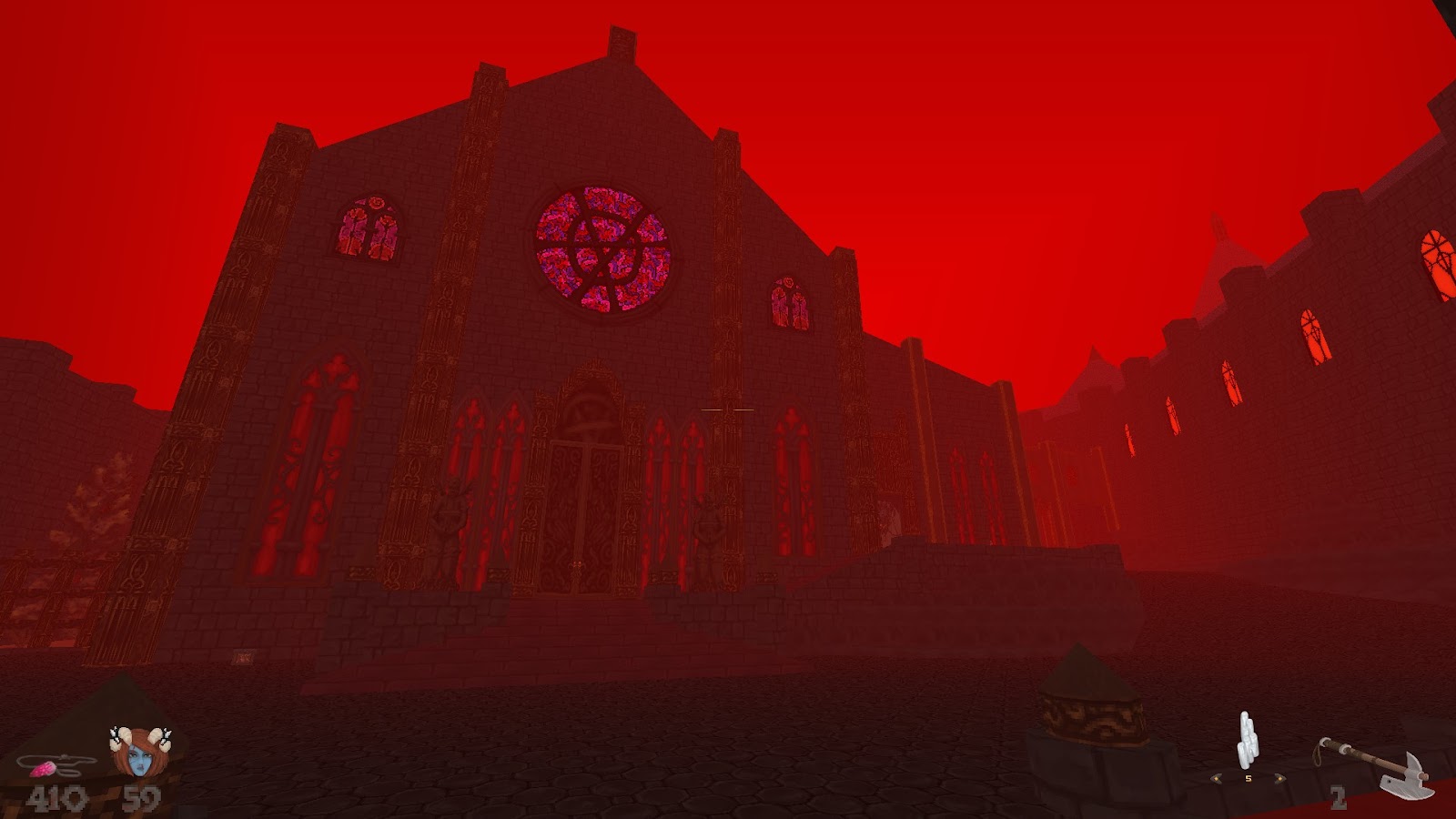

Hedon excels because it is aware of these nuances. Each weapon in your arsenal is a unique multi-faceted tool which enables more sophisticated encounter design. Each enemy presents a new and unique challenge when added atop previously existing tasks; these further complicate and reward well-planned play. Being continuously outnumbered forces you to play to your strengths and be mindful of the level around you, which is compounded when considering level hazards and other obstacles. Hedon is a game where the creativity of the level design is allowed to blossom because of its pure base mechanics. You can go from a sea of flame aboard an attacking fleet of cultist-filled ironclads, to navigating a bouncy castle filled with demons within an even larger demonesses’ mindpalace. These levels augment the more meat and potatoes engagements simply by existing, as you never know when a simple encounter is going to erupt into something more complex.

I explain in more detail than necessary because even in 2020 and every year thereafter, I was acutely aware of these strengths in Hedon. It kept me trying and retrying it even after embarrassingly bouncing off time and time again. Yet, Hedon doesn’t end there; it also takes inspiration from games like Arx Fatalis and Thief. Both are heavily systemic and demand deep respect for the world you’re occupying to excel. Hedon, not content with merely being a good retro shooter, endeavors to do the same.

Hedon instead puts you in a lavish and intricate world meant to simulate something real. To find your way you must read in-game lore, and be capable of extrapolating clues and direction from them. This explodes in complexity across Hedon’s second episode, Blood Rite. Approximately eight hours into an already substantive campaign, you are suddenly in the deep end with not one, but two open-world hubs. There are now shops, friendly npcs, quests with multiple outcomes, and accompanying AI companions — in the middle of this retro Doom-engine powered first-person shooter. Over the course of this new chapter — which is on its own nearly twice the length of its predecessor — you will do everything from seducing a demoness in her own house, to brewing potions in an ancient crypt for a wall sconce that wants energy drinks made of life and death. Such highlights made my own personal 30 hour playthrough feel eventful where I’ve otherwise been fatigued by shooter campaigns a tenth of the length.

With all of these positives, it begs the question then: what was so obstructive in the first place?

There are two sticking points where I can foresee players getting caught in this game. The first is relative directionlessness. Often, instead of utilizing the level design to push the player in the correct direction, the game trusts you to treat this as a real place. You must be immersed enough in the world to form long-term plans and use said plans to determine where you need to be. If, for example, you need to open a gate that is blocking your path, and find that it is missing a gear, you know what you need to achieve your goal. If in that same map you see some manner of forge or craft shop, you can reasonably assume that you’re going to have to make it yourself. Some players — and myself too, originally — take objection to this approach. FPS games, at their most simplistic, often don’t ask so much of a player. Having acclimated to Hedon’s approach, I can’t cite this as a flaw. Fully immersing myself and trusting in the world of this game ended up being the primary push to liking it as much as I do.

That trust is also an aspect of the other sticking point, one more complex than Hedon alone and one that transcends genre. The compulsion to avoid specific mechanics or items. Hedon borrows much of its DNA from adventure games; it gives you a massive number of items, each of which grants specific beneficial effects in combat. Playing Hedon well requires you to use these items to their fullest potential. For me, this was something of a learning curve. I had the pre-assertion that such items were tertiary to the game itself. There was, of course, pride involved but also anxiety. Often, I feared that using the items would be an excuse for the game to rug pull me later, punishing me for using something I thought was only there to help. Playing the game in this way elevates the difficulty much higher than was originally intended; simple combat encounters grind to a halt, and tactics become more conservative and boring. Even outside of Hedon I have caught myself succumbing to this behavior. This was the change in perspective mentioned earlier: I realized that electing to not interact with the greater part of a game’s mechanics was hampering my ability to say I was meaningfully engaging with the game at all. I realized that fear of trusting games was stopping me from connecting with them. Once I was able to acknowledge this flaw in myself, I was able to view such mechanics as not something to be avoided but something to embrace as an additional layer of complexity.

The biggest criticism I could aim at Hedon would be for its story. Compared to the outstanding ambience, it was all too easy for the characters and core conflict to slide from my mind. For the majority of Hedon’s first chapter, save for a few standout missions, you are predominantly seeing the world almost entirely in its aftermath. In Blood Rite, your character takes a much more proactive role, but the conflict remains relatively simplistic: orcs unite to kill demons which are a threat by the nature of their existence. Where this was a far harsher criticism in my prior review of Pathfinder: Wrath of the Righteous, here is much more muted. For myself, a first-person shooter having a story is augmentative rather than being a direct necessity. I am not of the more extreme opinion that they should be divested of stories entirely, but I do favor their removal when they interfere with the heart of the game. In Hedon, it’s muddied. The option to engage with the story is present, particularly in its second half, but frequently it seems to tacitly give you permission to not care. At my most reductive observation, it’s a boomer shooter about ventilating demons with the dangerous end of a shotgun; you’ve seen it before, probably several times this year. It is clear that the developer cares about the setting and has given thought to those who inhabit it, but the two sides of world exploration and visceral combat are unfortunately not married with a well-considered story. This matters very little in the end. The dual pillars of search and destroy fundamental to this game are sturdy; the story has the courtesy to not get in the way for those who—like myself—just want to revel in the experience.

In the end, Hedon was a conscious reminder to play games more earnestly, with more interest in what a game is actually attempting to achieve. We live in a time where many games become samey, not necessarily from a lack of drive to do something novel, but instead because people know what works. Like film motifs, this language becomes the cultural undercurrent to what a game is expected to be. Games which go against the grain are by their nature frictional, but are all the more likely to stand out as a result. Hedon manages to buck current trends, ironically by gazing back as much as it does. Hedon having the vision to avoid becoming something more approachable—and thus more forgettable—while also having strong fundamentals is key to its successes. As a game with clear passion made predominantly by a single person, I can’t help but advocate for it.

Good

"A Shotgun-Flamethrower is only your third weapon"

Hedon is an intriguing middle ground between immersive adventure and classic explosive first-person shooter action that will give you an outstanding time provided you are willing to truly engage with it.