Last year, I began developing a game with partners and close friends of mine. We started our project out of a shared disappointment in many of the management simulation games released in the past decade. Granted, I started and still work as the lead artist, but I often chime in on the design side as well. Most games fans remain as games fans, rarely jumping to the side of the creative. Sure, a designer must playtest their own game to ensure it works and feels good to play, and pretty much every game maker out there plays video games, but these roles are rather set in stone. For puzzle games, one would assume this relationship is even farther apart than usual. The designer knows all of the answers, so what fun remains in playing their own game?

Many puzzle developers view the act of creation itself as a sort of game. Rather than a typical developer-player relationship in which the developer can take any number of roles (the creator of a sandbox for the player, a narrator guiding the player through the story, etc, these features do exist within puzzle games as well yet their design pushes them towards a different role), a puzzle developer would prefer to restrain the puzzle to only the requisite parts required for the player to find its solution. Although the methods are different, they reach the same goal within the solution. Features such as alternate solutions are undesired “cheese”; unnecessary components are unhelpful “red herrings”. Many gamers call any interaction with one environment a “puzzle”, which often muddies these conventions. A two-way developer-player relationship very well could explain why puzzle games commonly, compared to other genres, have level creators. Even non-puzzle games such as Bloons Tower Defense 6 and Super Mario Maker 2‘s level creators have served as lovely homes for puzzle designers.

Such restrictive conventions would indicate a dull, emotionless genre and a lifeless developer community. After all, puzzles require logic, so a game that evokes grand emotions would seemingly clash with these conventions. On the contrary, a guided interactive experience allows the game to have dazzling, awe inspiring page-turn esque “reveals”. Reveals of information, mechanical tricks, and depth are so core to the emotions of puzzle solving experiences that designers like Adam Saltsman would once go as far as to call puzzle creators “revealologists… A good twist has nothing on a good reveal”. They are the mechanical version of a door opening to a new area, of the camera pulling back to a wide shot revealing a beautiful open landscape. Reveals impact players so much that I could argue they lead the charge in the oft-heard calls for “textless tutorials”. Yes, reveals are in anything designed, but I think nothing does them better than a great puzzle.

I watched my girlfriend play Can of Wormholes, and in a moment of sokoban movement fidgeting she discovered a specific setup that can make your worm tilt upwards and start climbing in the third dimension towards the camera. She was aghast. The ramifications of this technique would not be revealed to her for many more levels, but it haunted her like a mechanical Chekhov’s gun. However, to quote Adam Saltsman again, reveals themselves are not mechanics. Good, inspiring design in itself is impressive and worthwhile. However, reveals are noteworthy in how they influence the design process themselves. Ramifications about interactions between simple mechanics emerge to the game creator as they playtest and continue to create their work.

Most of the most impactful gaming moments for me in the past few years have been puzzle reveals. Some of them even involve big features going against the standard puzzle conventions I discussed earlier. Getting the bad ending in Void Stranger and discovering you need to beat the game without dying (or undoing) to progress (and then finding out I have barely scratched the surface of that colossal game), thinking I beat Bee Magic only to find out you need to cheese the game with only some of the several movement spells to unlock more… Such moments, which would otherwise seem like huge setbacks showing just how much you have left to go, lit a roaring blaze in my heart, unquenched until I discovered even more.

A smaller appeal (and a large sum of the audience being designers themselves) set the grounds for the lovely yet small puzzling community I’ve cherished lurking in. As the norm within the puzzle community is small, tightly designed games, and the roles of developer and player are blurred, it leads to some truly wonderful works of game design. Mechanical conversations slowly driven by money within the big industry contrast lightning fast developments between solo developers in these small cozy corners. I am overjoyed that some hardcore puzzle games like Blue Prince have gotten as big as they have. Watching others play Blue Prince when they are early on feels like I am watching a completely different game, silently wondering, “Do they know?”. Not just in the meta puzzles, but with small “tech” that heavily improves consistency in the roguelike aspect. I eagerly hold my breath when their eyes hold for a second too long on a noteworthy detail of a room.

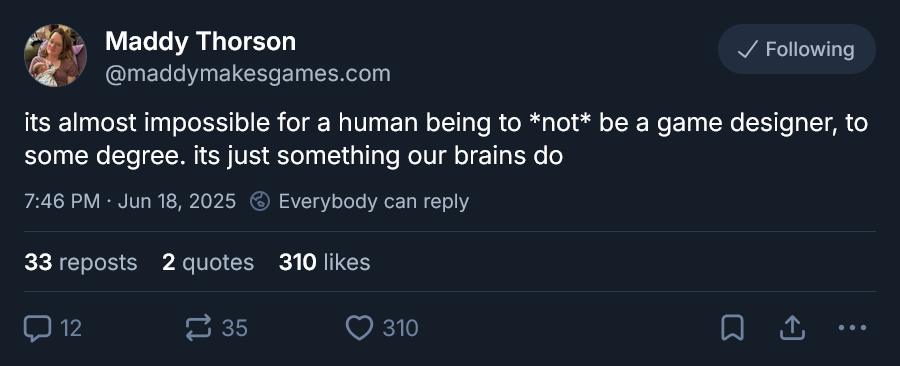

I am loving puzzle games more and more lately, perhaps because so much of my thinking is occupied by game design thoughts. So many of the most wonderful puzzle games last year like Gentoo Rescue, Ooo, the lovely Confounding Calendar collection, and much more have gone greatly underappreciated compared to many of the other big indie hits. Perhaps this designer mentality I enjoy taking while puzzling shows me that, to some degree, these games appeal most to gamers with a designer’s mindset. Not every music fan wants to be a musician, not every film fan wants to be a director, so it makes sense that most gamers do not care much to take this mindset. But yet, in the words of the great Maddy Thorson:

@maddymakesgames.com

its almost impossible for a human being to *not* be a game designer, to some degree. its just something our brains do

When game gifting season came around last year, I ended up giving a lot more puzzle games than usual. I badly want to share this joy of puzzling with my peers. If you wish toTo partake in the joy of puzzling with me, I find many of these great games from showcase youtube channels like Thinky Games and Icely Puzzles. Thinky Games also hosts Thinkycon, where the developers of these very showcased games discuss their design processes. It’s a developer talk convention, so not every presentation shines, but far more of them show insight than waffling. Listening to the inspiration behind this and that (alongside showing games to your friends) is the closest I can get to wiping my memory of a puzzle game and playing it all over again. Play more puzzle games in 2026, dear reader!

Penny is an art blogger, a poster, and an anime convention panelist who enjoys gaming subculture and old stuff.