Beyond Citadel is not a game for everyone. It contains horrific violence, gratuitous erotica, abandonment by the divine, incest, and other such extreme things. This review contains it in turn.

I thought it was necessary to convey it; I thought this, was art.

Let me tell you a story.

I was trapped in a shooting gallery at the bottom of a series of stairs. My enemies had the high ground, and I had no recourse but firing upward with a sniper rifle. It was a bolt-action, allowing me to crouch, evacuate the chamber, and ready another shot in relative safety. My shots were accurate, headshots all. The masses depleted, falling distantly in the 8x magnification scope until one remained. My hands fumbled, accidentally ejecting the round before firing it.

It fell, landing in a puddle of mutilated viscera. Reaching down, I realized that it still breathed: one of my earlier victims. Still under fire, I did what I needed to do. I dug through her bloody entrails and removed the cartridge. I dispensed it into the skull of her comrade some 130 meters away.

Looking down on her properly, I was forced to come to terms with what I had done. A grenade, delivered by my own hands, had deprived her of about two-thirds of her body. Limbs were removed, intestines dripping onto cold, utilitarian-steel floors. She panted in pained excoriation.

The axe in my off hand took care of the remaining thirty-three percent.

This is the world of Beyond Citadel.

Provocative as it is, talking about Beyond Citadel in such a fashion is something of a necessity. It is violence and intimacy inseparably linked. Talking around it or diminishing it would be misrepresenting it. I will say frankly, before even arriving at a conclusion, this will not be a game for everyone.

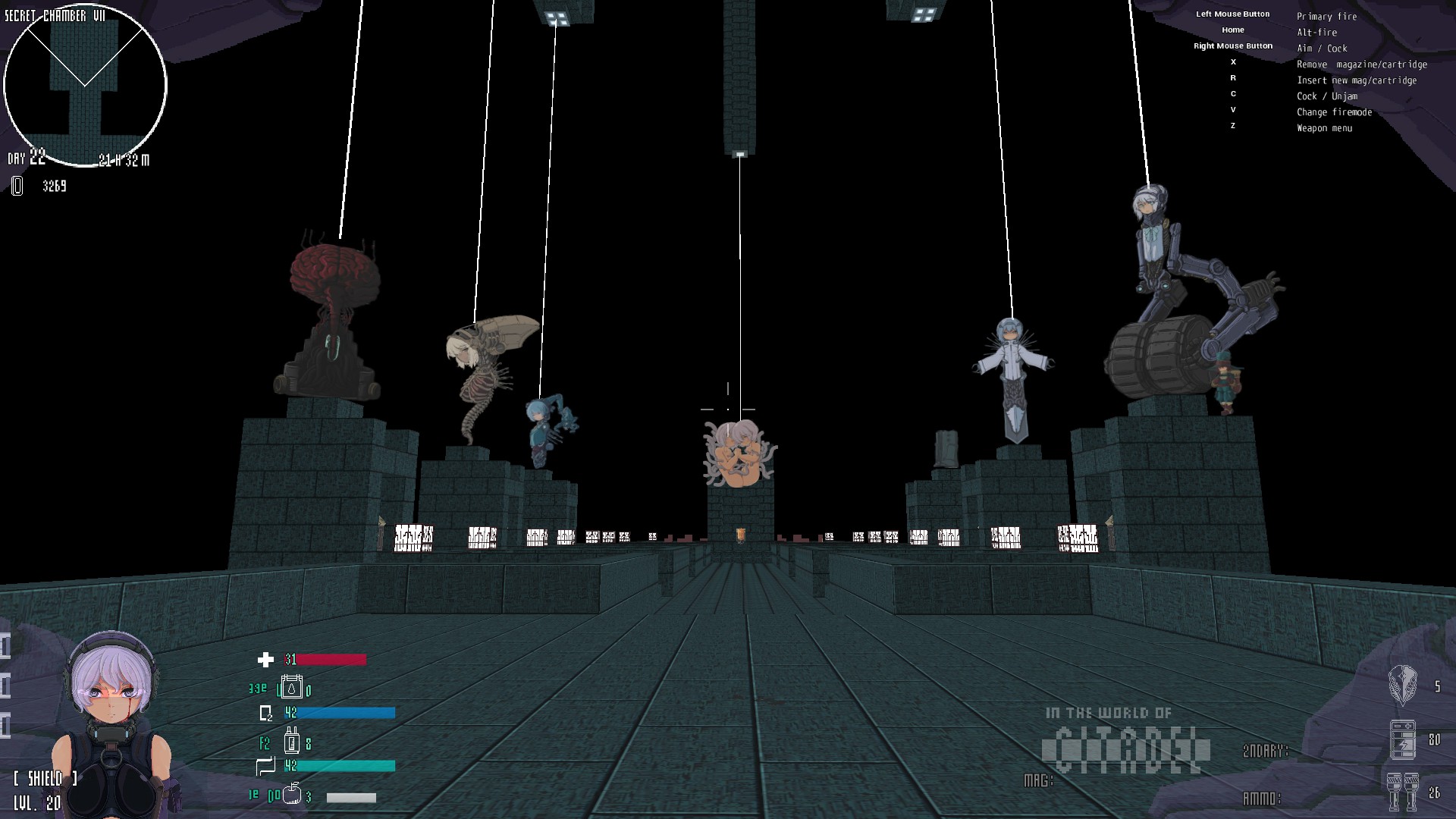

The game almost immediately pushes away those with basically any reservations around the use of gratuitous violence as an aesthetic choice. You might find yourself turned away by the eroticism before you even have a chance to see the violence. You look down and you see your own breasts prominently. You slide and approximately two-thirds of the screen are dedicated to the Thigh Zone™. Your armors are various forms of latex-coated tac gear, straps, and thigh boots swaddled with purple-toned sappenpanzer. And you kill hundreds.

If you possess even the slightest interest in this game, however—or, even more strangely—simply want to hear what I have to say on something you personally have no interest in, I encourage you to read onward.

Beyond Citadel is a 2025 Unreal-Engine-based first-person shooter made by developer Doekuramori and a sequel to the earlier 2019 release, The Citadel.

Compared to some of the games from my other reviews, I was intrigued with Beyond Citadel with relative immediacy. Rather than hearing about it through word of mouth or social media, I found it plainly sitting on the front page of Steam. My initial impressions were positive; I was immediately charmed with the visual aesthetics harkening back to games like Marathon and Outlaws. The “most-helpful” steam reviews informed me that this was a game for “eroguro sickos who will play this game one-handed.” It was in my library by the end of the day.

Like everything else in Beyond Citadel, it ties back to the violence.

So, let’s talk violence.

Violence as Violence

When first acquiring a firearm in Beyond Citadel, the first-time player will be immediately taken by the expected level of mechanical intimacy demanded. While it doesn’t have you fiddling with safeties or other such minutiae, it does intentionally separate the act of ejecting magazines from expected wrote actions like chambering rounds. Even gun jams, which typically manifest as little more than a period of waiting in other games, are interesting in Beyond Citadel. They require you to remove the jammed round from your gun—something which happens with growing frequency as the durability of your firearm depletes—all while being fired upon by dozens of enemy combatants. You must eye your ammunition pools while managing a hunger meter and blood-oxygen level, dancing between grenades and combatants with double-jumps, air-dashes, and super-jumps.

For a veteran of the genre, this is wonderful. It’s certainly one thing to play a game and wish that certain mechanics would just get the hell out of your way. Many other “realism” mechanics test my patience rather than requiring any real act of skill; control over needless busy work. There is just enough granularity on display here, that it feels like driving a manual car. Your control feels like power, rather than weakness. You feel the tactile bumping of your weapon slowly approaching empty; you drop a magazine to the ground, slamming another into place, cycling a round, before beginning the onslaught anew. Larger weapons, like the heavy machine gun, require multiple keystrokes to lift the cover, release the box magazine, then feed the weapon before they can be fired again.

All of this would be intriguingly tactile if nothing else, but this goes hand in hand with Beyond Citadel’s depictions of violent acts.

When you first play through the initial levels, you fight black, spidery creatures. You fire on them with a repeating Winchester-like rifle and tear through them with a heavy two-handed axe. They explode into giblets of a fashion that the average, seasoned FPS player will be utterly desensitized to. Levels pass, you fight these creatures, you familiarize yourself with the controls, you come to enjoy the gunplay. Perhaps, you have a wry giggle at the fact that you can stare downward and gaze at your own breasts, or the fact that your character is a stoic anime girl.

Then begins the first combat encounter with other human beings. You are, presumably, familiar with this transaction. You aim, you fire, they die; lead for life. But, that’s not exactly how it plays out here. The gunshots reverberate loud, and the sound design conveys that you are committing an atrocity. Their bodies depict contortions of agony, sprites twisted as limbs fly off torsos and gore splatters freely. On more than one occasion, you will realize that you have freed the upper half of someone’s torso from their body, leaving their ribs still standing, torn out of their exposed abdomen.

Many times I realized that my enemies weren’t actually dead. They laid on the ground, making the sound of distressed, pained panting.

I continued playing, getting to enemies which used firearms. Similar results, though to my surprise, some of them produced side-arms to fire upon me while in their downed state. I quickly became the kind of person that commits war crimes, the infamous double tap.

You also are not immune to the violence of this world. Dying was incredibly startling when it first occurred. A terrified, strangled, scream of death and a grotesque close up of my own intestinal tract. The body continues to degrade as you are fired upon, even in your downed state. Face, skull, torso, all are explosively worn away by bullets, until nothing but the backside of a skull and a spinal cord remain. I remember seeing the hollow, cavernous space where my own vacated brains used to be, and shivered.

Violence of this sort haunted every play session. This kind of thing immediately sticks with you. You can’t simply look away from it. I can’t segue into other matters; oh, the level design is also like so; oh, the bosses are a bit meh. Resultantly, even structuring this review has been a nightmare. In other games, our butcheries are simply expected things. You don’t shoulder the moral weight of enemies you slaughter, it was just an expected part of the game. The Martyr, Beyond Citadel’s taciturn protagonist, does not respond to these things in the least. The only one to shoulder the weight of what you have done is you. Violence becomes Beyond Citadel because ultimately it expresses the horrifying nature of violence. We fear it and enjoy it at the same time. Violence is awful; violence is entertainment. Both things can be true at once.

But Beyond Citadel does not stop at expressing a world of utter violence—the obverse of the coin is equally articulated.

Lust as Violence

On Beyond Citadel’s release, A small battalion of the least funny people you can imagine collectively pointed, laughed, and said “gooner shooter” at the same time before all patting one another on the back and calling it a day. As I mentioned previously, the erotic expression on display is, to some, overwhelming. Without overstating things, I will simply say that it doesn’t bother me. I’m far from the least susceptible person when it comes to being coerced to try something through the clarion call of a cartoon boob. I’m not going to launder my own opinions and pretend to be better than that; I’m not a teenager kicking an M-rated game under my bed before my parents notice I have something I shouldn’t.

When I talked around the very apparent eroticism of something like Hedon it was mostly because it had very little to do with what was immediately enjoyable about it. The giant, muscle-bound, ageless, beautiful orc women amounted to an aesthetic choice and little else; the game only acknowledges it in a passing explanation of why they are all ageless and beautiful. Here, I feel like there’s something a little more to it than just simple curb appeal.

While talking with a colleague about Beyond Citadel, I ended up thinking about limit experiences. To save myself from the inevitable horror of having to cite not one but three different philosophers, I will say simply this:

A limit experience is a sensation that touches the extremis of possible sensation; a point where things are divested of meaning, impossible to convey by words. In the conceptions of Georges Bataille, “divine ecstasy and extreme horror,” that being the expressions of perfect joy and perfect agony, are ultimately identical. The reason this comes to mind with Beyond Citadel should be immediately obvious. Violence is intentionally a horrifying act but one we—as players of games which use such violence—experience with regularity. Beyond Citadel achieves re-sensitization of violence through the lens of something uncomfortable—intentional eroticism.

The enemies which fall to the ground as the result of your dispensation of violence writhe in near orgasmic throes. A character may speak on the morality of your murders while wearing fetishistic versions of catholic nun habits. The dying moan as you liberate them from their mortality.

This correlation between sex and violence is not novel. Films such as Hellraiser, Alien, or the body-horror works of Cronenberg have used erotic imagery to trigger visceral discomfort in their audiences. The violence of Beyond Citadel would not be as impactful without the relief that its extreme sexuality casts upon it. In the realms of a fantasy, one can imagine the violent intrusion of an axe blade into one’s torso as being equal to an erotic penetration, rather than the cessation of life that it represents in the real world. Even in the more grounded world, the violence of the erotic can take the form of hardcore kink, BDSM sex, and other such extremes.

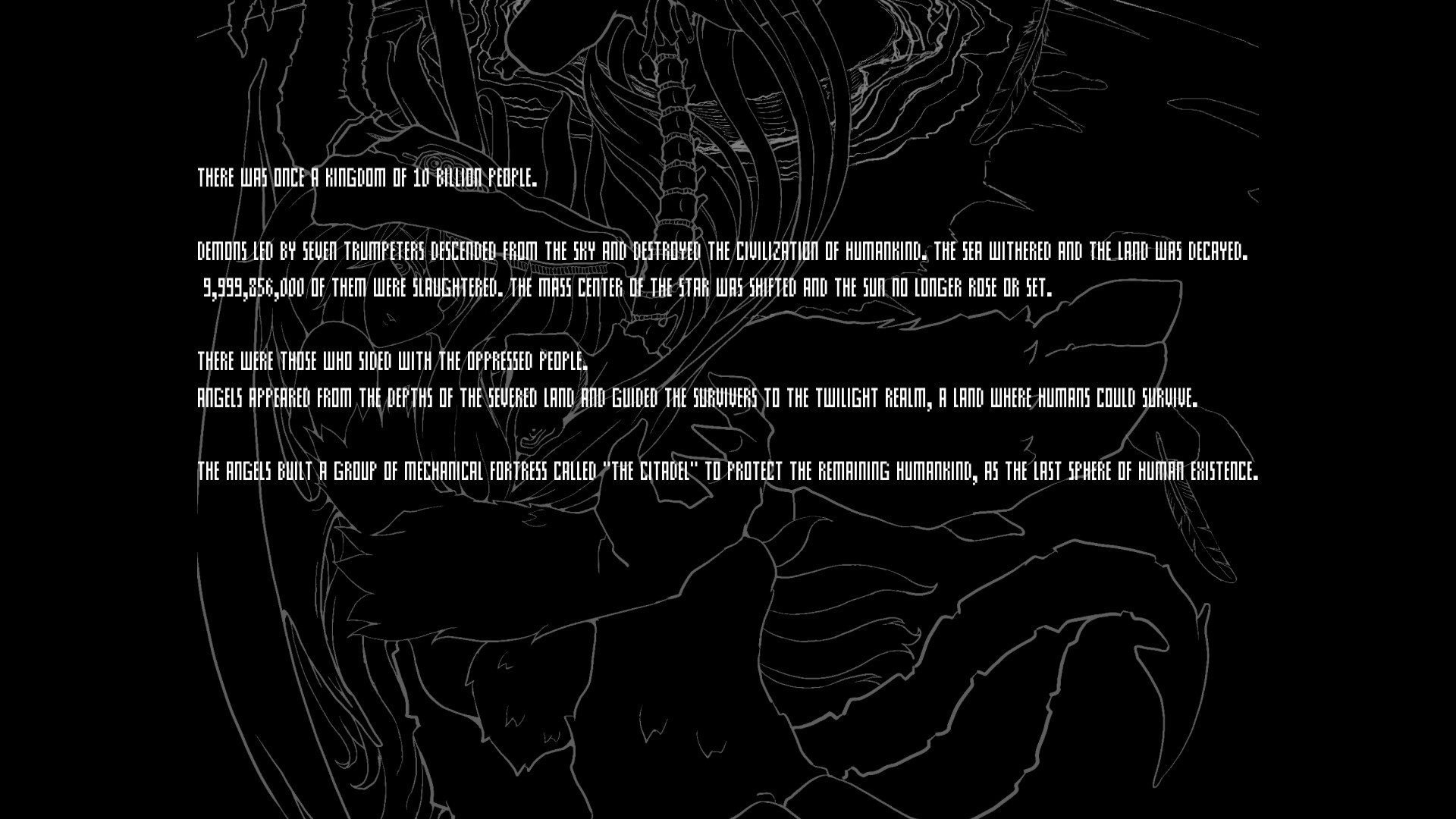

The story is expressed in this way as well. The world of Beyond Citadel, outside its steel-grey corridors and panting, ahegao-faced, dying women, is a place of transgression. Demons have become angels, angels demons, and God is decidedly absent in the whole affair. The world as we see it is an apocalyptic waste. The Martyr kills her way through what remains of humanity, brainwashed and deprived of ego—a fact that a character mentions to further absolve you of guilt. It becomes obvious through the completion of levels that what motivates the Martyr is also transgressive.

The story as it exists is difficult to immediately understand. It is buried in layers of intentional obtuseness and some poor translation. But as we progress, we learn of the incestuous relationship of the Martyr and her brother, that which lead to her role in the story. It is uncomfortable and largely uncriticized by the game itself.

Obviously, this too will be a stopping point for some people. “Atrocious violence and gratuitous sexuality are one thing, but incest is another,” one could say. The relationship is painful and grotesque, and it makes worse the lives of literally everyone involved. Yet, I think, to an extent, this is intentional. This is a world divested of all grace. You tear through what lives remain in this hellscape, thanked by what friendly NPCs remain for “your sacrifices.” Violence, lust, and love all have spectrums of appeal and horror, pleasure and pain. At no point did I think the journey of the Martyr was an admirable one—one that was going to end with a happy conclusion.

Within all of us lies the ability to participate in transgressive art without besmirching ourselves. Discomfort is not immorality; comfort is not peace. I exercised my ability to be uncomfortable with Beyond Citadel, and something meaningful can be derived from it.

Latex and Cordite

A major reason that I wanted to talk about Beyond Citadel in the first place was admittedly because of the conversation around it. While it currently has overwhelmingly positive reviews on Steam, most seem to either dejectedly talk around the “waifu stuff” or otherwise cheer in the predictable teenage boy kind of way.

What professional articles I have read, look at the most extreme content and either shrug, claiming it to be something good despite such content, or otherwise cite it as “a game for freaks.”

There are only so many ways I can tolerate being condescended to in such a fashion. Being offered some slop for sickos will work on me, of course—I am actually a freak—but I always feel a sense of passive resentment. I want to meet the game on the level it is at, not just tear the skin off a toy that is otherwise fun but has an aesthetic that I don’t like.

Let me reclaim the veneer of a review for myself here: I really really like Beyond Citadel. I like its gunplay; I like its strange nonsensical and completely subvertible level geometry; I like it for what it is trying to do; I like it for things it isn’t trying to do.

Beyond Citadel is a messy game with many flaws. My breathless, reverent chattering about sex and brutality should not convince you that this is a transcendent, holy experience. It is a rough gem. The game bugs out frequently, it crashes often, its bosses are thoughtless slogs, and in its back half I felt exhausted making my way through chapters. At the very least for the last point, I felt there was meaning to derive. This was a game made clearly by exactly the kind of person who wanted it to exist. The fatiguing hyper-indulgence of violence sticks to the palate. You feel the burdens of your hundreds of murders weighing on you and it clings like a film. This is a game about how violence can be cathartic, fun, sexual, fatiguing, and horrifying. The contradiction is the texture.

Admittedly, another reason that I wanted to talk about this game was because of the current media climate we find ourselves in. As a person who both enjoys erotic media and is friends with people who make it, or otherwise are in the industry of sex, the world has not been particularly kind to our sort lately. Censorship is rife and systemic, and many times it feels like people are cheering on the side of censorship whether they realize it or not.

“I am fine with seeing a man inverted by a rocket, but I’m not going to cast my eyes on some fucking goon-slop.”

The answer to this sentiment is that I don’t have an answer. Censorship in many cases is what any sufficiently fascist system is hungry for; when people willingly opt in, all the better. All hail the world where I can’t say fuck or watch fucking, but I can easily open a video game where I can split a man’s skull in half with an axe. This isn’t me engaging in unproductive what-about-ism; I want both to be available; I am against censorship in all its forms. Sometimes it just feels like we can but wriggle as we are put on the conveyor that will toss us into the gears of a machine that eats expression and produces commerical-friendly “product.”

The weird pseudo-machismo of violence is fragile while brought up against the weight of the erotic. Yes, rip and tear until it is done, ultra-violence, blood is fuel, I am a flesh automaton animated by neurotransmitters, and so on. Beyond Citadel says yes to all of that. Rip and tear, cut that woman’s limbs off, watch her brains dribble out from the hole you blew into her forehead, end her life when she tried to end yours. But it also does so as intentional horror and sexuality. Is it a problem now? To some, clearly, the answer is yes.

So in protest of that, I’ll say as I said before. Beyond Citadel is great. It’s not a masterpiece despite all its transgressions and lewd sensuality but because of them. As a person who has adopted violence as one would a fashion accessory—incorporating the aesthetics of brutality and darkness while remaining a peaceful person—it was exactly the kind of game I wanted when I wanted it. It goes up on the wall of things that I love very much and will recommend to very few.

How better then to end off this review with another transgressive quote from something I love. A song. “Jennifer” off the album Prowler in the Yard by Pig Destroyer:

“‘This is disgusting, it’s pornography’ exclaimed a pasty slug-like woman in a fur coat, vanilla ice-cream smeared across her double chin like a money shot. Countered a balding professor type in his mid-forties, his left hand stuffed crassly down the front of his pants.

‘No,

No,

No.

This is beautiful,

This is art.'”

Good

"A wedding band forged from a tac knife"

At once both repulsive and magnetic, Beyond Citadel is a violent, sexual, hateful, loving game.